Mold exposure is an increasingly recognized environmental health concern, often dismissed as merely an aesthetic issue or allergy trigger. However, emerging research reveals a far more complex interplay between mold toxins – known as mycotoxins – and human health, particularly concerning the disruption of our gut microbiome. This isn’t simply about feeling unwell after encountering mold; it’s about understanding how these microscopic fungal metabolites can fundamentally alter the delicate ecosystem within our digestive system, leading to a cascade of potential health problems that extend far beyond typical allergy symptoms. The implications are significant, as a healthy gut is foundational for overall well-being, impacting immunity, mental health, and even chronic disease risk.

The insidious nature of mycotoxin illness stems from their ability to bypass many conventional diagnostic methods, leaving individuals feeling dismissed or misdiagnosed. Unlike bacterial or viral infections with clear markers, the effects of mycotoxins are often subtle and widespread, mimicking other conditions. This makes identifying mold as the root cause challenging, especially given that exposure can occur in diverse environments – homes, workplaces, even food sources – without obvious visual signs of mold growth. The disruption to gut bacteria is a central component of this illness, acting as a key link between environmental exposure and systemic health impacts, making it vital to understand the mechanisms at play. Understanding functional dyspepsia and how it differs from typical indigestion or gas can also help differentiate symptoms.

Mycotoxins: A Deeper Look at the Culprits

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by molds as a defense mechanism or during their growth cycle. They aren’t inherently toxic to the mold itself, but rather represent chemical weapons used for competition in their environment. There’s a vast array of mycotoxins, each with varying degrees of toxicity and specific modes of action within the human body. Some of the most common mycotoxins associated with health problems include:

- Aflatoxins (produced by Aspergillus species) – potent carcinogens impacting liver function.

- Ochratoxin A (found in grains, coffee, wine) – nephrotoxic (kidney damaging).

- Fumoninsins (associated with corn and corn products) – linked to esophageal cancer and immune suppression.

- Trichothecenes (produced by Stachybotrys chartarum, “black mold”) – highly toxic, causing rapid immune response disruption.

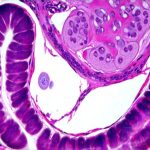

These mycotoxins don’t just stay in the gut; they are readily absorbed into the bloodstream, impacting multiple organ systems. However, the initial and often most significant impact is on the gut microbiome—the trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms residing within our digestive tract. This community isn’t merely a passive bystander but actively participates in digestion, nutrient absorption, immune regulation, and even neurological function. Mycotoxins directly target this delicate balance, leading to dysbiosis – an imbalance in gut microbial composition.

The mechanisms by which mycotoxins disrupt the gut are multi-faceted. They can directly inhibit bacterial growth, alter bacterial metabolism, and increase intestinal permeability (often called “leaky gut”). Increased permeability allows undigested food particles, toxins, and bacteria to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation. This creates a vicious cycle: inflammation further disrupts the microbiome, making it even more susceptible to mycotoxin damage, and exacerbating health problems. The impact isn’t limited to killing beneficial bacteria; mycotoxins can also promote the growth of harmful bacteria, shifting the ecosystem towards a pathogenic state. How to balance gut bacteria with diet is paramount for overall health.

Gut Microbiome & Immune Function: A Compromised System

A healthy gut microbiome is intrinsically linked to robust immune function. Approximately 70-80% of our immune system resides within the gut, constantly interacting with the microbial community. Beneficial bacteria help “train” the immune system to distinguish between friend and foe, preventing overreactions to harmless substances (like pollen or food) and mounting an effective response to genuine threats. Mycotoxin-induced dysbiosis significantly compromises this delicate balance.

When mycotoxins disrupt the gut microbiome, they reduce the diversity of beneficial bacteria that are crucial for immune regulation. This leads to decreased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate – metabolites produced by bacterial fermentation that nourish gut cells, reduce inflammation, and support immune function. A lack of SCFAs weakens the intestinal barrier, furthering permeability and contributing to systemic inflammation.

Furthermore, dysbiosis can activate inflammatory pathways within the gut lining. The resulting chronic low-grade inflammation isn’t just confined to the digestive system; it contributes to a wide range of health issues including autoimmune conditions, allergies, neurological disorders, and even mental health problems like anxiety and depression. The gut microbiome is no longer acting as an immune educator but instead becomes a source of constant immunological stimulation. This altered immune state makes individuals more susceptible to infections and less able to effectively fight off pathogens. Understanding the role of gut bacteria in managing nausea can offer further insights.

Addressing Gut Dysbiosis & Mycotoxin Exposure

Restoring gut health in the context of mycotoxin exposure is not a quick fix; it requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses both the source of exposure and the resulting microbial imbalance. It’s essential to remember that simply taking probiotics won’t necessarily solve the problem if the underlying mold exposure continues or the gut environment remains highly inflammatory.

- Identify & Eliminate Exposure: The first, and arguably most important step, is identifying and eliminating the source of mycotoxin exposure. This may involve professional mold inspection and remediation in homes or workplaces, avoiding mold-contaminated foods, and ensuring proper ventilation. It’s not always easy to pinpoint the exact source, but minimizing exposure is paramount.

- Support Detoxification Pathways: The body has natural detoxification mechanisms that can help eliminate mycotoxins. Supporting these pathways involves:

- Adequate hydration – water helps flush toxins from the system.

- Nutrient-dense diet – providing building blocks for liver detoxification enzymes.

- Liver support supplements (under professional guidance) – such as milk thistle or glutathione precursors.

- Restore Gut Microbiome Diversity: Once exposure is minimized, efforts can be directed towards restoring gut microbiome diversity:

- Dietary changes – incorporating fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut), prebiotic-rich foods (onions, garlic, bananas), and fiber-rich vegetables. How to rotate foods and avoid digestive fatigue from repetition or sensitivity is also a key consideration.

- Targeted Probiotic supplementation – Choosing probiotic strains specifically known to counteract mycotoxin effects or support immune function can be helpful, but it’s crucial to work with a healthcare professional to select the appropriate strains.

- Butyrate supplementation – Can help nourish gut cells and reduce inflammation if SCFAs are insufficient.

The Role of Binding Agents & Nutrient Support

Binding agents like activated charcoal or bentonite clay can be used, under careful medical supervision, to bind mycotoxins in the digestive tract, reducing their absorption into the bloodstream. However, it’s crucial to use these cautiously and for limited periods, as they can also bind essential nutrients if not managed properly. They are not a substitute for eliminating exposure.

Mycotoxin illness often depletes specific nutrients due to increased metabolic demands during detoxification processes and impaired nutrient absorption caused by gut dysbiosis. Key nutrients that may be depleted include:

- Vitamin D – crucial for immune function and inflammation regulation.

- B vitamins – essential for energy production and neurological health.

- Magnesium – involved in hundreds of enzymatic reactions, including detoxification.

- Selenium – a powerful antioxidant protecting against oxidative stress.

Addressing these nutrient deficiencies through diet or supplementation (under professional guidance) can help support the body’s recovery processes. It’s important to note that simply taking supplements isn’t enough; optimal absorption requires a healthy gut microbiome and adequate digestive function. How stress affects gut bacteria is also an important factor to consider.

Long-Term Management & Prevention

Navigating mycotoxin illness is often a long-term process requiring ongoing management and preventative measures. Regular monitoring of indoor air quality, maintaining proper ventilation in homes, and being mindful of food sources can help minimize exposure risks. Focusing on lifestyle factors that support overall health – stress management, adequate sleep, regular exercise – also strengthens the immune system and enhances resilience.

It’s vital to work with healthcare practitioners who are knowledgeable about mycotoxin illness and gut health. Conventional testing methods may not always detect low-level chronic exposure or accurately assess the extent of microbial imbalance. Advanced diagnostic tools, such as organic acid testing (OAT) and comprehensive stool analysis, can provide valuable insights into metabolic function and microbiome composition, guiding personalized treatment strategies. Ultimately, understanding the intricate relationship between mycotoxins, gut bacteria, and overall health is essential for empowering individuals to take control of their well-being and build a more resilient future. How doctors confirm gut damage from food allergies can also be relevant in complex cases.