Digestive sensitivity is an increasingly common complaint, manifesting in a wide spectrum of symptoms from bloating and gas to abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. Often dismissed as ‘just being sensitive,’ these experiences can significantly impact quality of life, affecting everything from social engagements to daily productivity. While many factors contribute to digestive discomfort – dietary choices, stress levels, underlying medical conditions – the health of the intestinal mucosa is often overlooked yet plays a pivotal role. This delicate lining acts as the first point of contact between our bodies and everything we ingest, and its integrity directly influences how efficiently we digest food, absorb nutrients, and maintain overall gut wellbeing.

The mucosal layer isn’t simply a passive barrier; it’s a dynamic ecosystem teeming with specialized cells, immune components, and microbial communities. When this system is compromised – through factors like inflammation, poor diet, or medication use – the resulting increase in permeability can trigger a cascade of events leading to heightened sensitivity and a host of digestive symptoms. Understanding the nuances of mucosal health allows us to move beyond symptom management toward more holistic strategies that support long-term gut resilience. It’s about recognizing that ‘digestive sensitivity’ isn’t necessarily a life sentence, but rather an indicator that this foundational system needs attention and care.

The Intestinal Mucosal Barrier: Structure & Function

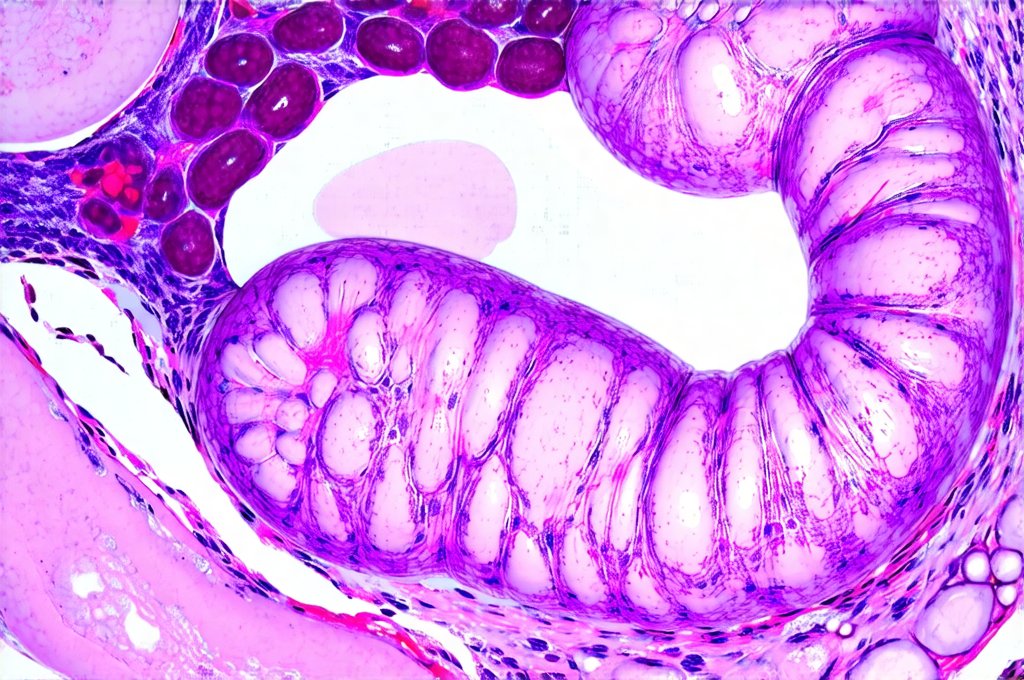

The intestinal mucosa is far more complex than a simple lining. It’s a multi-layered structure designed for optimal digestion and protection. At its core lies the epithelium – a single layer of cells responsible for nutrient absorption, secretion of digestive enzymes, and acting as a physical barrier against harmful substances. Beneath this epithelial layer resides the lamina propria, rich in immune cells like lymphocytes and macrophages, constantly monitoring the gut environment for threats. Further down is the muscularis mucosae, providing structural support and enabling movement within the intestinal tract. Finally, the outermost layer, the submucosa, contains blood vessels, lymphatic channels, and nerves crucial to maintaining mucosal health.

This barrier isn’t just physical; it’s also functional. Tight junctions between epithelial cells prevent unwanted substances from leaking into the bloodstream – a concept known as ‘intestinal permeability’ or often referred to as ‘leaky gut’. A healthy mucosa maintains selective permeability, allowing beneficial nutrients to pass through while blocking harmful toxins and undigested food particles. The mucus layer secreted by goblet cells within the epithelium acts as an additional protective barrier, trapping pathogens and lubricating the intestinal contents for smooth passage. This dynamic interplay between physical structure, functional components, and microbial interactions determines the overall integrity of the mucosal barrier and its ability to regulate what enters our bodies.

Beyond its immediate digestive functions, the mucosa plays a crucial role in immune regulation. Roughly 70-80% of our immune system resides within the gut, with the mucosa acting as a key interface between dietary antigens and the body’s defense mechanisms. This constant exposure to food proteins and microbial components necessitates a delicate balance between tolerance and response – allowing for efficient nutrient absorption while preventing inappropriate inflammatory reactions. Compromised mucosal health can disrupt this balance, leading to chronic inflammation and heightened sensitivity. Understanding digestive enzymes is key to maintaining gut function.

Factors Disrupting Mucosal Integrity

Many factors can contribute to the breakdown of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Diet is arguably one of the most significant. A diet high in processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats can promote inflammation and alter gut microbial composition, negatively impacting mucosal health. Conversely, a lack of fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and fermented foods deprives beneficial bacteria of their essential fuel source, weakening the barrier’s defense mechanisms. Incorporating fermented foods can help restore balance.

- Chronic stress is another major culprit. The gut-brain axis connects these two systems directly, meaning that psychological stress can profoundly impact digestive function and mucosal integrity. Stress hormones like cortisol can increase intestinal permeability and suppress immune function within the gut.

- Medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics can also disrupt the mucosa. NSAIDs have been shown to damage the epithelial lining, while antibiotics indiscriminately kill both harmful and beneficial bacteria, disrupting the delicate balance of the microbiome and increasing susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens.

- Infections, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), and even certain genetic predispositions can further compromise mucosal health, creating a vicious cycle of inflammation and sensitivity. Apple cider vinegar may also provide some relief for digestive issues.

The Microbiome’s Role in Mucosal Health

The gut microbiome – the trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms residing within our digestive tract – is inextricably linked to mucosal health. Beneficial bacteria play several vital roles in maintaining barrier function, including:

- Producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which serve as a primary energy source for colonocytes (the cells lining the colon) and strengthen tight junctions between epithelial cells.

- Competing with harmful pathogens for nutrients and space, preventing their overgrowth and reducing inflammation.

- Modulating immune function, promoting tolerance to food antigens and regulating inflammatory responses.

A diverse and balanced microbiome is therefore essential for a robust mucosal barrier. However, factors like diet, stress, and antibiotic use can disrupt this microbial ecosystem, leading to dysbiosis – an imbalance in gut bacteria composition. Dysbiosis often results in reduced SCFA production, increased intestinal permeability, and heightened inflammation, exacerbating digestive sensitivity. Supporting bile function is also important for overall digestion.

Strategies for Supporting Mucosal Health

Restoring and maintaining mucosal health requires a multi-faceted approach focused on addressing the underlying causes of disruption. Dietary modifications are paramount. Incorporating a wide variety of fiber-rich plant foods – fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – provides fuel for beneficial bacteria and promotes SCFA production. Reducing processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats minimizes inflammation and supports barrier function.

Beyond diet, managing stress levels is crucial. Techniques like mindfulness meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises, and regular physical activity can help regulate the gut-brain axis and reduce cortisol levels. Consider incorporating prebiotic foods (like garlic, onions, and bananas) to nourish beneficial bacteria and probiotic-rich fermented foods (like yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut) to introduce diverse microbial strains into the gut. Digestive enzymes can also aid in breaking down food for easier digestion.

Finally, identifying and addressing any underlying medical conditions or medication-related issues is essential for long-term mucosal health. This may involve working with a healthcare professional to explore alternative medications or address nutrient deficiencies. Prioritizing sleep, staying hydrated, and limiting alcohol consumption are also important lifestyle factors that support overall digestive wellbeing and contribute to a resilient intestinal mucosa. It’s about viewing the gut not as an isolated organ, but as an integral part of our overall health ecosystem – one that deserves consistent care and attention. Synbiotics offer a combined approach to improving gut health. Additionally, consider the role of bitter foods in stimulating digestion.