Chronic gas issues—bloating, distension, flatulence, and discomfort—are surprisingly common, affecting a significant portion of the population. Many individuals dismiss these symptoms as a normal part of digestion, attributing them to dietary choices or simple sensitivities. However, persistent and excessive gas can be debilitating, impacting quality of life and often signaling underlying imbalances within the digestive system. While food intolerances and dietary habits undoubtedly play a role, increasingly research is pointing towards a more fundamental issue: the integrity of the intestinal barrier and its associated permeability. This article will delve into the connection between gut permeability – often called “leaky gut” although that term can be misleading – and chronic gas production, exploring how a compromised barrier function can lead to digestive distress and what potential avenues exist for support.

The digestive system is far more than just a processing plant for food; it’s a complex ecosystem teeming with trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome. This microbial community plays a vital role in nutrient absorption, immune regulation, and overall health. A healthy gut barrier—formed by tightly joined intestinal cells—selectively allows nutrients to pass into the bloodstream while preventing undigested food particles, toxins, and bacteria from escaping into the body. When this barrier becomes compromised, increased permeability can disrupt this delicate balance, triggering inflammation and contributing to a cascade of symptoms, including chronic gas. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for addressing the root causes of digestive discomfort rather than simply managing the symptoms. Considering the impact of the gut microbiome on overall health is a great starting point.

The Intestinal Barrier: Structure and Function

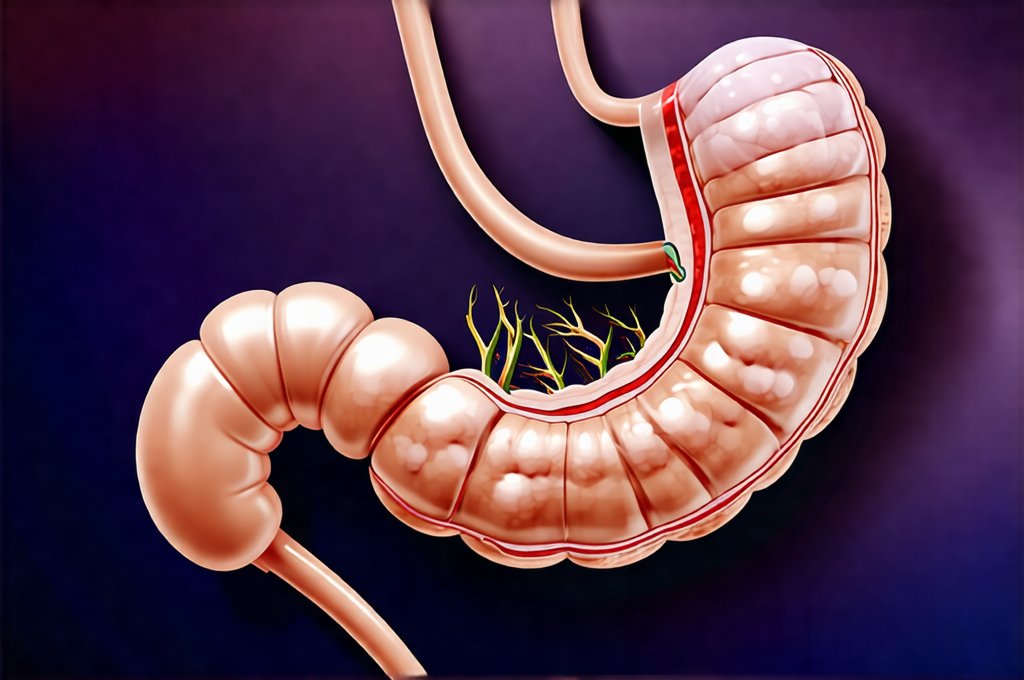

The intestinal barrier isn’t just one structure; it’s a multifaceted system comprised of physical, immunological, and microbiological components working in harmony. At its core are the enterocytes, specialized cells that line the small intestine. These cells are connected by tight junction proteins – structures that act like “mortar” between bricks, ensuring a secure seal. A healthy barrier maintains this tight connection, allowing for efficient nutrient absorption and preventing unwanted substances from entering systemic circulation. The mucus layer provides another level of protection, acting as a physical barrier and nourishing beneficial gut bacteria. Furthermore, the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) – representing a significant portion of the body’s immune system – constantly monitors the intestinal environment, responding to threats while maintaining tolerance to harmless substances.

When this intricate system is functioning optimally, it allows for selective permeability. This means that only specifically sized and processed nutrients are allowed through, while larger molecules—like undigested food proteins or bacterial toxins—remain within the gut lumen. However, factors like stress, poor diet (high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats), infections, and certain medications can disrupt this delicate balance, weakening tight junctions and increasing intestinal permeability. This increased permeability isn’t necessarily a constant state; it can fluctuate based on these influencing factors, making diagnosis challenging but highlighting the importance of addressing underlying causes rather than just treating symptoms. Understanding intestinal pressure is also key to understanding gut health.

A compromised barrier leads to several downstream effects that contribute to chronic gas. For example, when undigested food particles “leak” into the bloodstream, the immune system recognizes them as foreign invaders and mounts an inflammatory response. This inflammation can further damage the intestinal lining, creating a vicious cycle of increased permeability and immune activation. The presence of these undigested foods also provides more fuel for bacteria in the gut, leading to excessive fermentation and gas production.

Factors Contributing to Increased Gut Permeability

Identifying the factors that contribute to gut permeability is essential for developing targeted strategies to support intestinal health. One significant contributor is dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbiome. A diverse and balanced microbial community helps strengthen the intestinal barrier, while a lack of diversity or overgrowth of harmful bacteria can weaken it. This imbalance can be caused by factors like antibiotic use (which indiscriminately kills both beneficial and harmful bacteria), chronic stress, and a diet low in fiber and high in processed foods.

- Antibiotics: Disrupt gut flora, reducing microbial diversity

- Stress: Increases cortisol levels, impacting barrier function

- Diet: Lack of fiber starves beneficial bacteria; processed foods promote inflammation

Another key factor is chronic inflammation, which can be triggered by various sources, including food sensitivities, infections, and autoimmune conditions. Inflammatory molecules directly damage tight junction proteins, increasing permeability. Leaky gut isn’t necessarily the cause of inflammation itself but often exacerbates it. Furthermore, certain medications, such as NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), can also contribute to increased permeability by damaging the intestinal lining. Finally, zonulin, a protein released in response to various stimuli, is believed to play a role in regulating intestinal permeability. Elevated zonulin levels are associated with increased barrier function and have been linked to autoimmune diseases and digestive disorders. Gut health impacts many aspects of overall wellbeing.

The Role of Fermentation & Gas Production

Chronic gas isn’t simply about the amount of gas produced; it’s about where it’s being produced, and what kind of gases are involved. When undigested carbohydrates reach the colon, they become a feast for gut bacteria, leading to fermentation – a natural process, but one that can be excessive in cases of increased permeability. This fermentation produces various gases, including hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide, which contribute to bloating, distension, and flatulence. The specific composition of gases produced varies depending on the individual’s microbiome and dietary habits.

- Hydrogen: Produced by many bacteria; associated with diarrhea

- Methane: Produced by methanogens; can slow gut motility leading to constipation

- Carbon Dioxide: Contributes to bloating and abdominal discomfort

Increased permeability allows for more undigested food particles to reach the colon, providing a greater fuel source for fermentation. Moreover, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) – a condition where excessive bacteria reside in the small intestine – can exacerbate gas production by fermenting carbohydrates prematurely. SIBO is often linked to gut permeability as it’s easier for bacteria to migrate upwards when the barrier function is compromised. The resulting gases can cause significant discomfort and interfere with nutrient absorption. Digestive enzymes can sometimes help mitigate these issues.

Dietary & Lifestyle Strategies for Support

While addressing gut permeability often requires a comprehensive approach, dietary and lifestyle modifications can play a significant role in supporting intestinal health and reducing gas production. A cornerstone of this approach is adopting an elimination diet to identify potential food sensitivities or intolerances that may be contributing to inflammation and increased permeability. This involves removing common trigger foods (such as gluten, dairy, soy, corn) for a period of time and then gradually reintroducing them one at a time while monitoring for symptoms.

Beyond elimination diets, incorporating gut-healing nutrients into the diet can also be beneficial. These include:

- L-glutamine: An amino acid that supports intestinal cell repair

- Collagen: Provides building blocks for gut lining tissues

- Zinc: Essential for maintaining tight junction integrity

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Reduce inflammation and support barrier function

Furthermore, managing stress is crucial, as chronic stress negatively impacts gut health. Techniques like mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and regular exercise can help reduce cortisol levels and promote a healthy gut environment. Prioritizing sleep, staying hydrated, and limiting alcohol consumption are also essential lifestyle factors that contribute to overall digestive wellness. Physical activity is another important aspect of maintaining good gut health. It’s important to remember that addressing gut permeability is often a long-term process requiring patience, consistency, and potentially the guidance of a qualified healthcare professional. Sometimes, finding humor can help cope with chronic digestive issues. Finally, understanding FODMAPs can also provide helpful insights.