Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a remarkably common condition affecting millions worldwide, often presenting as heartburn, regurgitation, and difficulty swallowing. While commonly attributed to acid reflux – the backflow of stomach acid into the esophagus – the picture is frequently more nuanced than initially appears. Many individuals experience symptoms mimicking GERD, but where traditional acid-suppressing treatments provide limited relief. This suggests alternative or additional mechanisms at play, and one increasingly recognized culprit is bile reflux—the upward flow of bile from the duodenum (small intestine) into the stomach and potentially even the esophagus. Understanding the role of bile in these seemingly “GERD-like” symptoms is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

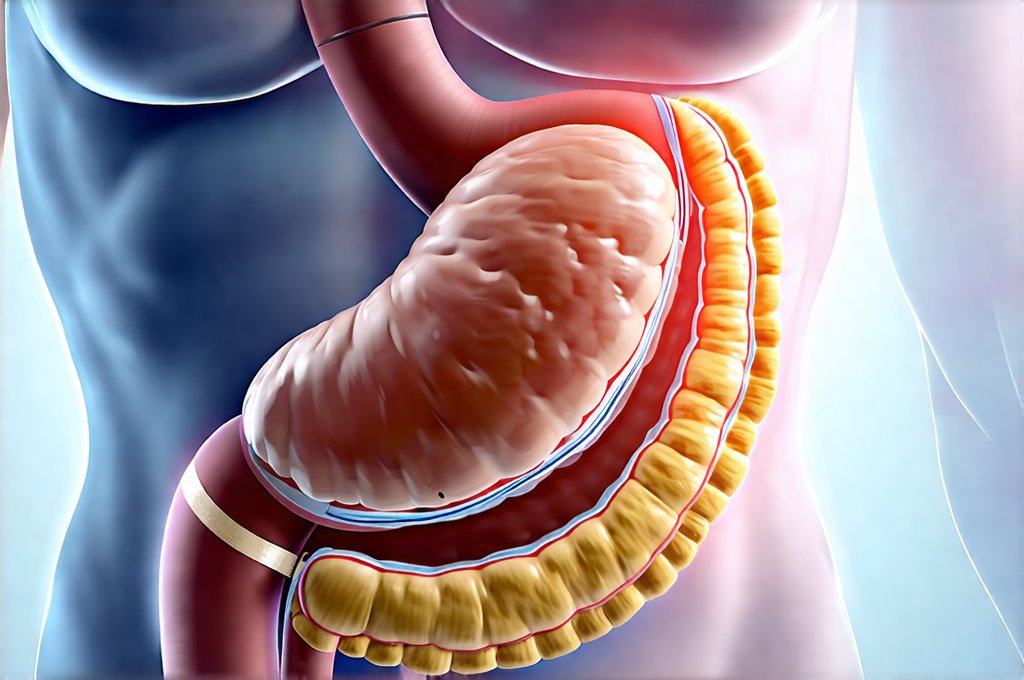

The digestive system is a carefully orchestrated process, with each fluid – acid, enzymes, and bile – playing a specific role. When this delicate balance is disrupted, it can lead to a wide range of gastrointestinal issues. Bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, aids in the digestion and absorption of fats. Normally, bile flows from the gallbladder into the duodenum, where it mixes with food. However, several factors can cause bile to travel backwards, entering the stomach and sometimes reaching the esophagus, leading to a condition called bile reflux disease (BRD). It’s important to note that BRD isn’t always present alongside acid reflux; it often occurs independently or as a secondary issue complicating GERD. This distinction is vital for appropriate treatment strategies.

Understanding Bile Reflux Disease

Bile reflux disease differs significantly from traditional acid reflux in its underlying mechanisms and the damage it can inflict. While stomach acid primarily causes erosive esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus), bile’s impact is more insidious and often leads to different types of esophageal damage. Acid’s corrosive nature tends to target the upper portion of the esophagus, whereas bile seems to affect the entire length, including the lower regions. This difference can make diagnosis challenging as standard acid-suppressing medications may not alleviate symptoms or prevent further complications. Identifying BRD requires a careful evaluation of symptom patterns and diagnostic testing beyond typical GERD assessments.

Bile is significantly more toxic to esophageal cells than gastric acid. It disrupts the protective mucosal barrier, causing inflammation and potentially leading to metaplasia—a change in cell type. Over time, chronic bile reflux can increase the risk of Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous condition. The symptoms of BRD often overlap with GERD, making differentiation difficult without proper investigation. Common complaints include: – Heartburn that doesn’t respond well to acid-reducing medications – Nausea and vomiting (sometimes containing bile) – Abdominal pain – particularly in the upper abdomen – A bitter or sour taste in the mouth – Chronic cough – Hoarseness It’s also important to understand that BRD is frequently seen after certain surgical procedures, such as gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy), or gastric bypass surgery. Understanding the role of bile acids can help with diagnosis and treatment.

The precise mechanisms driving bile reflux are complex and not fully understood, but several factors contribute. Dysfunction of the pyloric valve – the muscle separating the stomach from the duodenum – allows bile to flow backward into the stomach. Similarly, a weakened lower esophageal sphincter (LES) can allow both acid and bile to reach the esophagus. Post-surgical changes in anatomy can also disrupt normal digestive flow. Importantly, BRD isn’t always about the quantity of bile refluxed; it’s often about its composition and how long it remains in contact with the esophageal lining. Bile acids are particularly damaging, and their prolonged exposure exacerbates inflammation and cellular damage. The role of fiber can also impact digestion.

Diagnosing Bile Reflux: Challenges and Methods

Diagnosing bile reflux is notoriously difficult because many standard GERD tests focus solely on acid levels. Traditional pH monitoring primarily measures acidity, failing to detect or quantify bile present in the esophagus. This can lead to misdiagnosis and ineffective treatment. A comprehensive approach is essential, incorporating a detailed medical history, symptom assessment, and specialized diagnostic testing. Patients should clearly communicate their experiences to their healthcare provider, emphasizing symptoms that differ from typical acid reflux presentations.

Several diagnostic tools are employed, though none offer a perfect solution: – Bile acid monitoring: This involves placing a catheter in the esophagus to measure bile acid concentrations over 24 hours. It’s more challenging than pH monitoring and less widely available but provides direct evidence of bile reflux. – Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): This procedure uses a flexible scope to visualize the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, looking for signs of bile-induced damage or inflammation. Biopsies can be taken to assess cellular changes like metaplasia. However, visual evidence of bile reflux during EGD is often limited. – Gastric emptying studies: These evaluate how quickly food empties from the stomach, which can indirectly suggest issues with digestive flow and potential for backflow. – Heidelberg Capsule pH monitoring: While primarily assessing acid levels, some newer versions can also detect alkaline reflux events that may indicate bile presence. Understanding the role of histamine in IBS symptoms is important to rule out other conditions.

The interpretation of diagnostic results requires expertise. A positive bile acid test or evidence of bile-related esophageal damage during EGD strongly suggests BRD. However, it’s important to remember that occasional, small amounts of bile reflux are normal. The clinical significance lies in frequent, substantial reflux causing symptoms and/or esophageal damage. Furthermore, the absence of a definitive diagnostic finding doesn’t necessarily rule out BRD, especially if symptoms are compelling and other causes have been excluded. A skilled clinician will integrate all available information—symptoms, test results, medical history—to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Managing acid reflux can also be impacted by stress.

Treatment Approaches for Bile Reflux

Treatment for bile reflux is more complex than for acid reflux due to the different mechanisms involved and the limited efficacy of traditional acid-suppressing medications. The primary goal is to minimize bile exposure to the esophagus, reduce inflammation, and prevent long-term complications like Barrett’s esophagus. Lifestyle modifications are often the first line of defense. These include: – Avoiding foods that exacerbate symptoms (often fatty or fried foods) – Eating smaller, more frequent meals – reducing stomach distension – Remaining upright for several hours after eating – Elevating the head of the bed during sleep – Losing weight if overweight or obese

Medications play a role, but their effectiveness is variable. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a bile acid commonly used to dissolve gallstones, can sometimes help neutralize bile acids in the stomach and esophagus, reducing inflammation. However, its benefits are not universally observed. Cholestyramine, a bile acid sequestrant, binds to bile acids in the intestine, preventing their reabsorption; this may reduce the amount of bile available for reflux, but it also has significant side effects and can interfere with nutrient absorption. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) – commonly used for GERD – are less effective for BRD because they target acid production, not bile. However, some patients find that PPIs help indirectly by reducing overall esophageal irritation. Aloe vera may offer some relief alongside other treatments.

Surgical intervention is usually reserved for severe cases or when medical management fails. Procedures aimed at strengthening the LES or diverting bile flow may be considered. These surgeries carry risks and are typically recommended only after careful evaluation and consideration of potential benefits. Ultimately, managing BRD requires a personalized approach, tailored to the individual’s symptoms, diagnostic findings, and response to treatment. Regular follow-up with a gastroenterologist is essential to monitor progress and adjust the treatment plan as needed. It’s crucial to remember that self-treating or relying solely on over-the-counter remedies can delay accurate diagnosis and potentially worsen complications. Understanding the role of bile in digestion will help patients understand their condition.