The human body is an incredibly complex ecosystem, and increasingly, research reveals just how much of our overall health hinges on the trillions of microorganisms living within us – particularly in our gut. For decades, we’ve viewed bacteria primarily as potential pathogens to be fought off, but this perspective is undergoing a radical shift. We now understand that these microbial communities, collectively known as the gut flora or microbiome, are integral to nearly every physiological process, from digestion and nutrient absorption to immune function and even mental wellbeing. A healthy gut microbiome isn’t simply about the absence of “bad” bacteria; it’s about a diverse and balanced community that actively supports our health. Disruptions in this delicate balance, known as dysbiosis, are increasingly linked to a wide range of chronic diseases, including autoimmune conditions.

The connection between the gut and systemic health is so profound that the gastrointestinal tract is often referred to as the “second brain.” This isn’t merely metaphorical; there’s a direct biochemical link – the gut-brain axis – facilitating constant communication between the two. When the gut microbiome becomes imbalanced, it can trigger a cascade of events leading to chronic inflammation, which many scientists now believe lies at the root of numerous autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues, and while genetics play a role, environmental factors—including the state of our gut flora—are crucial in determining who develops these conditions. Understanding this intricate relationship is vital for developing more effective strategies for prevention and treatment.

The Gut Microbiome and Inflammation

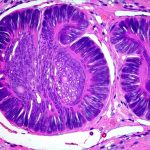

The gut microbiome’s influence on inflammation isn’t about directly causing it in all cases; rather, it’s about modulating the immune system’s response. A diverse microbiome actively trains the immune system to distinguish between harmless substances (like food) and genuine threats (like pathogens). This training process relies heavily on short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), metabolites produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber. SCFAs, like butyrate, propionate, and acetate, have potent anti-inflammatory effects:

- Butyrate is a primary energy source for colon cells, strengthening the gut barrier and reducing “leaky gut.”

- Propionate influences glucose metabolism and can reduce inflammation systemically.

- Acetate impacts brain function and immune regulation.

When dysbiosis occurs – often due to factors like poor diet, antibiotic use, or chronic stress – the production of beneficial SCFAs decreases, while populations of pro-inflammatory bacteria may increase. This leads to a weakened gut barrier, increased intestinal permeability (often called “leaky gut”), and subsequent systemic inflammation as bacterial components and undigested food particles enter the bloodstream. The immune system then launches an attack on these foreign invaders, creating a state of chronic low-grade inflammation that can contribute to autoimmune disease development. In essence, a compromised gut microbiome can inadvertently trigger an overactive and misdirected immune response. You can learn more about leaky gut and how it relates to inflammation here.

Furthermore, the gut flora directly influences the balance between different types of T cells – key players in the immune system. Certain bacteria promote the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which suppress immune responses and prevent autoimmunity. Others may encourage the proliferation of pro-inflammatory T helper cells (Th1 and Th17), increasing the risk of autoimmune reactions. Maintaining a balanced microbiome is therefore essential for maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing inappropriate attacks on healthy tissues. A healthy gut isn’t just about what bacteria are present, but also about their relative abundance and how they interact with the immune system. Understanding gut biome diversity is crucial for a strong immune response.

Autoimmunity: A Gut-Driven Component?

The link between gut health and autoimmune diseases is becoming increasingly recognized across a spectrum of conditions. While research continues to unravel the specifics for each disease, common threads emerge pointing to the gut’s significant role. For example, in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis – dysbiosis precedes inflammation and plays a crucial part in its perpetuation. Specific bacterial imbalances have been identified that correlate with disease flares and severity. Similarly, in type 1 diabetes, alterations in the gut microbiome are observed even before the onset of autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. The link between gut microbiota and disease is becoming clearer with each study.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune condition affecting the joints, also shows a strong connection to gut health. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with RA often exhibit altered gut microbial composition compared to healthy controls. Specific bacteria can either exacerbate or mitigate inflammation associated with RA, influencing disease progression and response to treatment. Even neurological autoimmune conditions, like multiple sclerosis (MS), are beginning to be understood through the lens of gut-brain axis dysregulation. Changes in the microbiome have been linked to increased intestinal permeability and subsequent immune cell infiltration into the brain, contributing to demyelination – a hallmark of MS.

The complexity lies in the fact that autoimmunity isn’t caused by one single factor; it’s a multifaceted interplay between genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and immune dysregulation. However, the gut microbiome is emerging as a key modulator of these factors, influencing both the development and progression of autoimmune diseases. The potential for therapeutic interventions targeting the gut microbiome – such as dietary changes, probiotics, prebiotics, or even fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) – is therefore garnering significant attention. Considering gut microbiota and obesity can also impact autoimmune conditions.

Dietary Strategies for Gut Health

Diet plays an arguably central role in shaping the composition and function of the gut microbiome. A diet rich in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats can promote dysbiosis, while a whole-foods based diet supports microbial diversity and beneficial bacterial growth. Here are some key dietary strategies:

- Increase Fiber Intake: Dietary fiber is the primary food source for many beneficial gut bacteria. Aim for 25-35 grams of fiber per day from sources like fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains.

- Limit Processed Foods & Sugar: These foods often contain ingredients that disrupt the microbiome and promote inflammation.

- Include Fermented Foods: Yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha are rich in probiotics – live microorganisms that can colonize the gut and improve microbial balance.

However, it’s important to note that dietary interventions aren’t one-size-fits-all. Individuals with autoimmune conditions may have specific sensitivities or intolerances that require personalized approaches. Identifying food triggers through elimination diets under the guidance of a healthcare professional can be beneficial. Focusing on an anti-inflammatory diet is often a good starting point, prioritizing whole, unprocessed foods. It’s also important to address any concurrent digestive issues that might be exacerbating inflammation.

The Role of Probiotics and Prebiotics

Probiotics and prebiotics are two strategies frequently used to support gut health, but they operate through different mechanisms. Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when consumed in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. They can help restore microbial balance, improve gut barrier function, and modulate immune responses. However, it’s crucial to choose probiotic strains carefully as different strains have different effects. A healthcare professional can guide you toward appropriate strains based on your specific needs.

Prebiotics, on the other hand, are non-digestible fibers that serve as food for beneficial bacteria in the gut. They promote the growth and activity of these bacteria, leading to increased SCFA production and improved gut health. Common prebiotic sources include onions, garlic, asparagus, bananas, and oats. Combining probiotics and prebiotics – a strategy known as synbiotic therapy – can enhance their effectiveness. It’s important to remember that simply taking probiotics isn’t a guaranteed fix; a healthy diet and lifestyle are still foundational. Understanding acute versus chronic indigestion can also help you tailor your approach.

Future Directions & Research

Research into the gut microbiome is rapidly evolving, revealing new insights into its complex interplay with inflammation and autoimmunity. One promising area of investigation is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), which involves transferring fecal matter from a healthy donor to a recipient with dysbiosis. FMT has shown remarkable success in treating recurrent Clostridium difficile infection and is being explored as a potential therapy for autoimmune conditions, although more research is needed.

Another emerging field is the use of personalized microbiome-based therapies. This approach involves analyzing an individual’s gut microbial composition to identify specific imbalances and then tailoring interventions – such as dietary changes or targeted probiotic supplementation – to restore balance. Furthermore, researchers are investigating the role of viral communities within the gut (the virome) and their influence on immune function. The future of autoimmune disease treatment may very well lie in harnessing the power of the gut microbiome to modulate immune responses and restore health. As our understanding deepens, we can expect to see more sophisticated and effective strategies for preventing and managing these debilitating conditions. The relationship between migraines and digestive upset is another area of growing interest within this field.