Gastrointestinal distress is a remarkably common complaint, touching nearly everyone at some point in their lives. The frustrating part isn’t necessarily having symptoms – bloating, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits are all familiar experiences – but rather pinpointing the underlying cause. Is it simply excess gas, a normal byproduct of digestion, or something more serious like inflammation indicating an underlying condition? This differentiation is crucial for appropriate treatment and management, yet often elusive because many symptoms overlap. Patients frequently struggle to articulate their experience clearly, and doctors face the challenge of teasing out subtle differences through careful questioning and targeted diagnostic testing.

The difficulty arises from the fact that gas and inflammation can mimic each other remarkably well. Gas distension causes discomfort, cramping, and a feeling of fullness—symptoms easily mistaken for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or other inflammatory conditions. Conversely, inflammation itself can alter gut motility leading to increased gas production. This complex interplay demands a nuanced approach to diagnosis beyond just symptom assessment. Doctors rely on a range of tests, from simple observations during physical exams to sophisticated imaging techniques and laboratory analyses, to unravel the source of digestive discomfort and develop effective treatment plans. The goal isn’t always to eliminate gas entirely (it’s an unavoidable part of digestion!), but to understand if it’s a primary issue or secondary to something more concerning happening within the gastrointestinal tract.

Differentiating Through Physical Examination & Initial Assessments

A thorough physical examination is often the first step in differentiating between gas and inflammation. This isn’t just a cursory check; it involves careful palpation – feeling the abdomen – to assess for tenderness, distension (swelling), and masses. A doctor will listen with a stethoscope to bowel sounds, noting if they are hyperactive (suggesting increased motility potentially related to gas or inflammation) or hypoactive/absent (which can signal more serious issues like obstruction). The location of the pain is also important; while both gas and inflammation can cause widespread discomfort, certain areas may be more indicative of specific problems. Initial questioning focuses on symptom characteristics: how long have symptoms been present? What makes them better or worse? Are there any associated symptoms like fever, weight loss, blood in stool, or fatigue? These initial assessments provide vital clues but are rarely definitive enough to make a diagnosis independently.

Beyond the physical exam, doctors often begin with relatively simple and non-invasive tests. A detailed patient history is paramount here. This includes dietary habits – identifying potential trigger foods that might exacerbate gas production – and medication review, as some medications can contribute to GI upset. Initial blood work typically includes a complete blood count (CBC) to look for signs of inflammation (elevated white blood cell count), anemia (which could suggest chronic bleeding from inflammation), and markers of general health. A C-reactive protein (CRP) test is frequently ordered; CRP is an acute phase reactant, meaning levels rise in response to inflammation throughout the body. Elevated CRP isn’t specific to the gut – it can be elevated with any inflammatory process – but it provides a starting point for further investigation. Fecal occult blood tests are used to screen for microscopic bleeding which would suggest intestinal inflammation or ulceration. Understanding food combining principles can also help identify dietary triggers.

The initial assessments help doctors create a differential diagnosis, meaning a list of possible causes for the symptoms. Based on these findings, they can then decide whether more specialized testing is warranted to rule out serious conditions and pinpoint the source of discomfort. It’s important to remember that many people experience gas without any underlying inflammation, and often simple dietary adjustments or over-the-counter remedies are sufficient. The goal of this initial phase isn’t necessarily to find inflammation but to rule it out as a primary concern before proceeding with investigations focused solely on gas-related issues. Considering mindful eating during meals can also minimize discomfort.

Advanced Testing for Inflammation

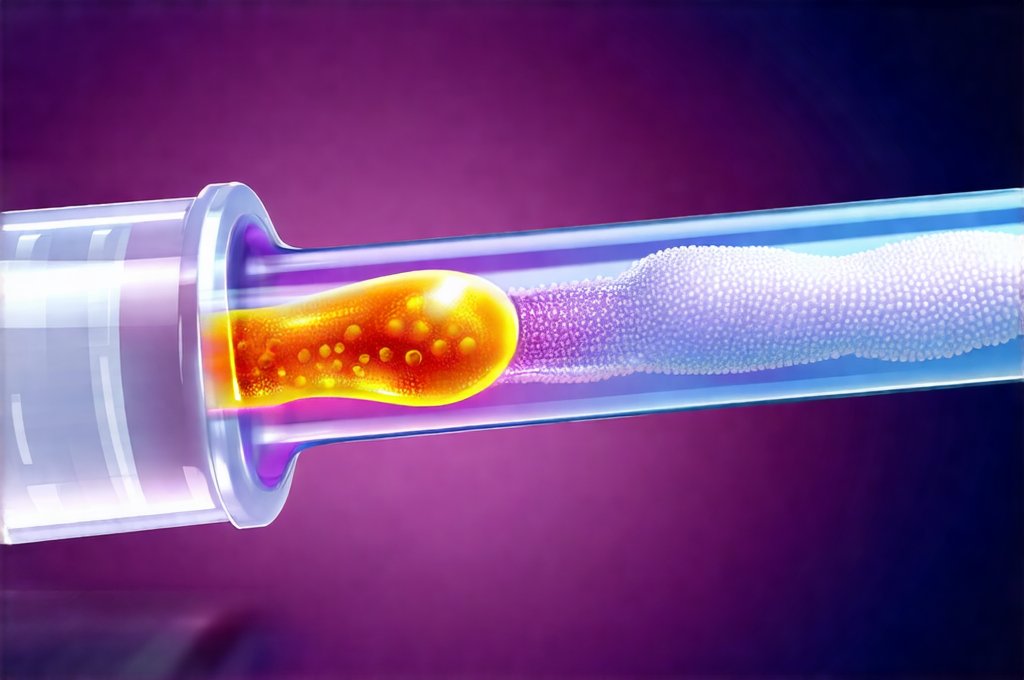

If inflammation is suspected, doctors will turn to more advanced testing methods. One crucial test is colonoscopy, where a flexible tube with a camera is inserted into the rectum to visualize the entire colon. During a colonoscopy, biopsies can be taken – small tissue samples – and examined under a microscope for signs of inflammation, ulceration, or other abnormalities characteristic of IBD (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) or microscopic colitis. Colonoscopies are highly effective at identifying inflammatory changes but require bowel preparation which can be unpleasant for the patient.

Another important test is endoscopy (also known as esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD), which allows visualization of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). Similar to colonoscopy, biopsies can be taken during endoscopy to assess for inflammation caused by conditions like gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, or Celiac disease. These procedures are often performed concurrently if there’s concern about inflammation in both the upper and lower GI tract. The choice between colonoscopy and endoscopy (or performing both) depends on the patient’s symptoms and the doctor’s clinical suspicion of where the inflammation might be located. Identifying sulfur-related gas can also narrow down potential causes.

Beyond visual assessments, stool tests can provide valuable information about gut inflammation. Fecal calprotectin is a protein released by neutrophils – a type of white blood cell – during inflammation in the intestines. Elevated fecal calprotectin levels are highly suggestive of intestinal inflammation and help differentiate between inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), where calprotectin levels are typically normal. Furthermore, stool cultures can identify infectious causes of inflammation like bacterial or parasitic infections which would require targeted antibiotic or antiparasitic treatment. These advanced tests allow doctors to move beyond suspicion and confirm the presence (or absence) of inflammation with a high degree of accuracy. Abdominal massage can provide temporary relief while undergoing testing.

Imaging Techniques & Further Differentiation

Imaging techniques play a crucial role in assessing the extent and location of inflammation, as well as identifying potential complications. Computed tomography (CT) scans provide cross-sectional images of the abdomen, allowing doctors to visualize the bowel wall thickness, presence of abscesses or fistulas (abnormal connections between organs), and other signs of inflammatory disease. CT enterography – a specialized CT scan focusing on the small intestine – is particularly useful for evaluating Crohn’s disease, which often affects this part of the digestive tract. However, CT scans involve radiation exposure, so their use must be carefully considered, especially in younger patients or those requiring frequent imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers an alternative to CT with no ionizing radiation. MRI enterography is increasingly used for evaluating Crohn’s disease due to its superior ability to visualize soft tissues and detect subtle inflammatory changes in the small bowel. While MRI scans are generally safe, they can be more time-consuming than CT scans and may not be suitable for patients with certain metallic implants. The choice between CT and MRI often depends on individual patient factors and the specific clinical question being addressed.

Finally, capsule endoscopy is a relatively new technique that involves swallowing a small capsule containing a camera. As the capsule travels through the digestive tract, it transmits images to a recorder worn by the patient. Capsule endoscopy is particularly useful for evaluating the small intestine, which can be difficult to visualize with colonoscopy or standard endoscopy. It’s often used when other tests have been inconclusive or to investigate bleeding from an unknown source. While extremely helpful, capsule endoscopy doesn’t allow for biopsy collection. Prebiotic-rich foods can support gut health during testing and beyond. Many find that following smart eating habits helps manage symptoms year round. Activated charcoal can also provide some relief from gas. By combining these imaging techniques with laboratory findings and clinical assessments, doctors can build a comprehensive picture of the patient’s GI health and accurately differentiate between gas-related symptoms and underlying inflammation.

It is important to reiterate that this information is for general knowledge and informational purposes only, and does not constitute medical advice. It is essential to consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.