The gut microbiome—the vast ecosystem of trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms residing in our digestive tract—is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of overall health. For years, it was largely overlooked, but modern research demonstrates its profound influence extends far beyond digestion, impacting immunity, mental wellbeing, chronic disease risk, and even nutrient absorption. Traditionally, assessing gut health meant focusing on symptoms like bloating or constipation. However, proactive monitoring through specific, measurable metrics offers a more comprehensive understanding of this vital system, allowing for targeted interventions and preventative strategies. A yearly check-in with your doctor regarding these metrics isn’t about chasing perfection; it’s about establishing a baseline, tracking changes, and being informed about potential areas to support your long-term health.

This shift toward quantifiable gut health assessment is driven by advancements in testing technologies and growing awareness among healthcare professionals. It moves beyond subjective experiences and provides objective data points that can guide personalized recommendations. While self-diagnosing or attempting drastic dietary changes based on online information isn’t advisable, understanding what your doctor can assess annually empowers you to be an active participant in your health journey. This article will outline key gut health metrics a physician can track, offering insights into their significance and how they contribute to a holistic view of your wellbeing. It’s important to remember that these tests are most useful when interpreted within the context of your individual medical history, lifestyle, and any existing symptoms.

Stool Analysis: Unveiling the Microbial Landscape

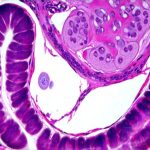

Stool analysis, often considered the gold standard for gut health evaluation, provides a snapshot of the microbial composition residing in your colon. It’s far more sophisticated than simply looking for pathogens; modern stool tests utilize techniques like 16S rRNA gene sequencing to identify and quantify different bacterial species present. This allows for an assessment of diversity – the number of different types of bacteria – which is a key indicator of gut health, as greater diversity generally correlates with resilience and improved function. Beyond identifying specific organisms, analysis can also reveal imbalances known as dysbiosis, where harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial ones.

The information gleaned from stool analysis isn’t just about identifying ‘good’ or ‘bad’ bacteria. It provides insight into metabolic functions carried out by the microbiome. For example, tests can detect levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) – metabolites produced when gut bacteria ferment fiber – which are crucial for colon health, immune regulation and overall wellbeing. Furthermore, markers of inflammation, like calprotectin, can indicate underlying intestinal inflammation even before symptoms become obvious. This early detection is invaluable in preventing chronic conditions. Understanding how doctors track changes can be a great first step.

It’s important to note that stool tests aren’t without limitations. Microbial composition can fluctuate based on diet, medication use (especially antibiotics), and other factors. Therefore, a single snapshot isn’t always representative of long-term gut health. However, when combined with regular monitoring and lifestyle adjustments, it provides valuable insights for personalized interventions. Discussing the results with your doctor is crucial to understand their relevance in your specific context. Considering whether eliminating dairy could help is also a good idea.

Breath Tests: Assessing Digestion & Fermentation

Breath tests are a non-invasive way to assess carbohydrate malabsorption and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). These tests rely on the principle that when undigested carbohydrates reach the colon, they’re fermented by bacteria, producing gases like hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide. These gases are absorbed into the bloodstream and exhaled in the breath – making them detectable through a simple breath sample collection process.

The most common breath test is the Lactose Breath Test, which determines if you have lactose intolerance—a deficiency of lactase enzyme needed to digest lactose (milk sugar). Similarly, Fructose and Sorbitol Breath Tests assess malabsorption of these sugars. Elevated gas levels during these tests indicate impaired digestion and potential symptoms like bloating, gas, diarrhea or abdominal pain after consuming these carbohydrates. SIBO breath testing is more complex, usually involving a glucose or lactulose solution to stimulate bacterial fermentation in the small intestine. An abnormally high rise in hydrogen or methane levels suggests an overgrowth of bacteria where they shouldn’t be – the small intestine.

While highly valuable, breath tests also have caveats. False positives and negatives can occur due to variations in testing protocols, individual metabolism, and preparation guidelines (fasting is usually required). Moreover, SIBO diagnosis based solely on breath tests is often debated, as it doesn’t pinpoint the cause of the overgrowth, only its presence. Therefore, breath test results should always be interpreted alongside clinical symptoms and other diagnostic findings. A doctor can show you what your doctor checks during a physical exam.

Inflammatory Markers in Blood

Inflammation is a natural part of the immune response, but chronic inflammation is linked to numerous health problems, including gut disorders. Several blood tests can provide insight into systemic inflammation levels, offering clues about gut health status. C-reactive protein (CRP) is one such marker, produced by the liver in response to inflammation anywhere in the body. Elevated CRP levels can indicate ongoing inflammation, which may be related to gut dysbiosis or intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”).

Another important inflammatory marker is fecal calprotectin, mentioned earlier in relation to stool analysis. However, blood tests assessing serum amyloid A (SAA) can also provide a systemic view of inflammation triggered within the gut. It’s crucial to understand that these markers aren’t specific to the gut; they reflect overall body inflammation. Therefore, interpreting them requires considering other factors like infections or autoimmune conditions. Regular monitoring of these markers over time is more informative than a single reading, helping to track changes and assess the effectiveness of interventions. You might also want to explore if gut health influence your immune cycles.

Nutrient Absorption & Vitamin Levels

A healthy gut is essential for optimal nutrient absorption. If the microbiome is compromised or intestinal permeability is increased, it can interfere with the body’s ability to absorb vital vitamins and minerals. Blood tests assessing levels of key nutrients like vitamin D, B12, iron, folate, and zinc can reveal deficiencies that might be linked to gut dysfunction. For example, low vitamin B12 levels are often seen in individuals with SIBO or inflammatory bowel disease, as bacteria can compete for this nutrient in the small intestine.

Furthermore, assessing fat malabsorption through stool tests (specifically fecal elastase) can indicate pancreatic insufficiency or issues with bile acid metabolism – both of which impact digestion and nutrient uptake. Checking for deficiencies isn’t just about addressing symptoms; it’s about ensuring your body has the building blocks it needs to function optimally. Supplementation should always be guided by a healthcare professional based on test results and individual needs.

Intestinal Permeability (Leaky Gut) – Emerging Assessments

The concept of “leaky gut”—increased intestinal permeability—has gained significant attention, although research is ongoing. It refers to the loosening of tight junctions between cells in the intestinal lining, allowing undigested food particles, toxins and bacteria to leak into the bloodstream. While directly measuring intestinal permeability isn’t a routine test yet, some assessments are emerging. Zonulin is a protein that regulates these tight junctions; elevated levels in stool or blood may indicate increased permeability.

Another approach involves assessing lactulose/mannitol ratio (LMR) in urine after consuming these sugars. Lactulose is poorly absorbed and primarily passes through the gut when permeability is normal, while mannitol is readily absorbed. An abnormal LMR suggests compromised intestinal barrier function. It’s important to emphasize that testing for leaky gut is still evolving, and interpretations require caution. It’s not a diagnosis in itself, but rather a potential indicator of underlying issues requiring further investigation and targeted interventions like dietary modifications or gut-healing protocols recommended by your physician. Some people also wonder if gut health influence their mood.

These metrics provide a starting point for understanding the complex world of gut health. Regular monitoring, combined with personalized guidance from your doctor, can empower you to take proactive steps toward a healthier digestive system and overall wellbeing. Also consider how doctors track changes in your gut over time.