Constipation, a prevalent digestive issue affecting millions globally, extends beyond merely infrequent bowel movements. It represents a disruption in the delicate equilibrium of our gastrointestinal (GI) system, with far-reaching consequences for overall health. Often dismissed as an inconvenience, chronic constipation can significantly alter the complex microbial ecosystem residing within our gut – the gut microbiome – and simultaneously trigger systemic inflammation. Understanding this intricate relationship is crucial not only for effective management of constipation itself but also for preventing downstream health complications linked to both a dysbiotic microbiome and chronic inflammatory states. The impact isn’t simply about discomfort; it’s about the fundamental interplay between our digestive system, our microbial inhabitants, and our immune response.

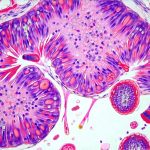

The gut microbiome, comprising trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms, plays an essential role in numerous physiological processes including nutrient absorption, vitamin synthesis, immune regulation, and protection against pathogens. A healthy microbiome is characterized by diversity – a wide range of species coexisting harmoniously. When constipation occurs, this delicate balance can be severely disrupted, leading to alterations in microbial composition and function. These changes aren’t merely passive consequences; they actively contribute to the perpetuation of constipation itself, creating a vicious cycle where altered microbiota exacerbate symptoms and further compromise gut health. The longer constipation persists, the more pronounced these effects become, potentially impacting systemic inflammation levels and overall well-being.

Constipation & Microbiome Dysbiosis: A Two-Way Street

Constipation fundamentally alters the environment within the colon. Reduced fecal transit time means nutrients remain in the large intestine for an extended period. This provides a different food source for microbes than what they’re accustomed to, favoring certain species over others. Specifically, populations of bacteria that thrive on undigested carbohydrates and proteins increase while those dependent on quicker fiber fermentation diminish. This shift often leads to a reduction in microbial diversity – a hallmark of gut dysbiosis – which is associated with impaired immune function and increased susceptibility to disease. Moreover, the slower movement allows for an overgrowth of potentially pathogenic bacteria, further exacerbating the imbalance.

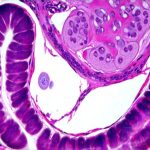

The relationship between constipation and microbiome composition isn’t unidirectional. It’s a two-way street. While constipation alters the microbial environment, changes in the microbiome can also worsen constipation. For example, reduced production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by beneficial gut bacteria – due to their decreased abundance – compromises colonic motility. SCFAs like butyrate are essential for maintaining gut barrier integrity and stimulating peristalsis (the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the digestive tract). Without sufficient SCFA production, stool becomes harder and more difficult to pass, perpetuating the cycle of constipation.

Furthermore, an increase in gas-producing bacteria is frequently observed in constipated individuals. This can lead to bloating, abdominal discomfort, and a sense of fullness – symptoms that often accompany constipation. The resulting distension can further inhibit colonic motility, adding another layer of complexity to the problem. Restoring microbial balance through dietary interventions and potentially probiotic supplementation (under professional guidance) is therefore crucial for breaking this cycle and alleviating constipation symptoms. Understanding how gut inflammation can further help in addressing these issues.

Inflammatory Markers & Gut Health in Constipation

Chronic constipation isn’t simply a lack of bowel movements; it’s often accompanied by low-grade systemic inflammation. This inflammation stems from several sources, all interconnected with the altered microbiome. A compromised gut barrier – frequently seen in dysbiosis – allows bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to “leak” into the bloodstream, triggering an immune response. This phenomenon is known as leaky gut or increased intestinal permeability. The body recognizes LPS as a threat and activates inflammatory pathways, resulting in elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

The impact of these inflammatory markers extends beyond the gut. Elevated CRP, for instance, is a key indicator of systemic inflammation and has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and even certain cancers. Similarly, chronic activation of immune cells due to constant exposure to bacterial products can lead to immune dysregulation and impaired host defense mechanisms. Importantly, the inflammatory response triggered by constipation isn’t merely a consequence of gut permeability; it’s also driven by the altered microbial metabolites produced in a dysbiotic environment. For example, an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory metabolites can exacerbate inflammation throughout the body. This is why hormonal birth control effects on digestion should be considered as well.

Addressing constipation, therefore, requires not just relief from symptoms but also strategies to mitigate the associated inflammation. This involves restoring gut barrier integrity through interventions like dietary changes (increasing fiber intake, reducing processed foods) and potentially supplementation with compounds that support gut health – again, under professional guidance. The goal is to reduce bacterial translocation, dampen the inflammatory response, and promote a more balanced microbiome composition.

Dietary Fiber & Microbial Modulation

Dietary fiber isn’t just about “roughage” – it’s a crucial prebiotic, meaning it provides nourishment for beneficial gut bacteria. Different types of fiber support different microbial populations, highlighting the importance of consuming a diverse range of plant-based foods. – Insoluble fiber (found in whole grains and vegetables) adds bulk to stool, promoting faster transit time and reducing constipation. – Soluble fiber (found in oats, beans, and fruits) ferments in the colon, producing SCFAs that nourish gut cells and improve motility. Increasing fiber intake gradually is essential to avoid bloating and gas; rapid increases can actually worsen symptoms.

The type of fiber matters significantly. Resistant starch, a type of carbohydrate resistant to digestion in the small intestine, selectively promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. These bacteria play a vital role in SCFA production and immune regulation. Furthermore, consuming a variety of plant-based foods ensures a broader spectrum of prebiotics, fostering greater microbial diversity. It’s important to note that individuals with certain digestive conditions may need to adjust their fiber intake based on tolerance and professional advice. Understanding a gluten-free diet can also help those with sensitivities.

The gut microbiome’s response to dietary fiber is highly individualized. Factors like genetics, existing gut composition, and overall health status influence how effectively someone utilizes fiber. Personalized nutrition approaches – tailoring dietary recommendations based on individual microbial profiles – are gaining traction as a promising strategy for optimizing gut health and alleviating constipation symptoms.

Probiotics & Constipation Relief

Probiotic supplementation aims to introduce live microorganisms into the gut, potentially restoring microbial balance and improving digestive function. However, the effectiveness of probiotics varies significantly depending on the strain, dosage, and individual’s microbiome composition. – Bifidobacterium lactis strains have shown promise in reducing constipation symptoms and improving stool consistency in some studies. – Certain Lactobacillus strains may also offer benefits, but more research is needed to determine optimal strains for constipation relief.

It’s crucial to understand that probiotics aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution. What works for one person might not work for another. The gut microbiome is incredibly complex and individualized, making it difficult to predict how someone will respond to probiotic supplementation. Furthermore, probiotics should be considered an adjunct to other strategies – such as dietary changes and increased physical activity – rather than a standalone treatment. Always consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen, especially if you have underlying health conditions or are taking medications. Dental health also plays an important role in digestion.

Recent research suggests that synbiotics – combinations of probiotics and prebiotics – may be more effective than either alone. The prebiotic component provides nourishment for the introduced probiotic bacteria, enhancing their survival and colonization in the gut. This synergistic approach holds promise for improving microbial balance and alleviating constipation symptoms.

Stress Management & Gut-Brain Axis

The gut and brain are intricately connected via the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network that influences both physical and mental health. Chronic stress can significantly disrupt this axis, negatively impacting gut motility, microbiome composition, and immune function. – Stress hormones like cortisol can alter intestinal permeability, increasing the risk of bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation. – Stress can also reduce blood flow to the digestive system, slowing down transit time and contributing to constipation.

Implementing stress management techniques – such as mindfulness meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises, or spending time in nature – can help regulate the gut-brain axis and improve digestive function. Regular physical activity is another effective way to manage stress and promote gut health. Exercise increases intestinal motility and reduces inflammation. Creating a routine that prioritizes relaxation and self-care is essential for maintaining both mental and digestive well-being. Emotional eating can also contribute to these issues, as stress impacts digestion.

Furthermore, addressing underlying psychological factors – such as anxiety or depression – may be necessary to effectively manage chronic constipation. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help individuals develop coping mechanisms for stress and improve their overall quality of life. A holistic approach that addresses the physical, emotional, and mental aspects of health is crucial for long-term management of constipation and its associated complications. Understanding how cold weather impacts digestion can also be helpful.