Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), commonly known as acid reflux, is typically associated with heartburn, indigestion, and perhaps a chronic cough. Most people envision these symptoms affecting the chest and stomach areas, understandably so given the origin of the condition. However, increasingly healthcare professionals are recognizing that GERD can manifest in surprisingly distant parts of the body – one such area being the neck. This connection isn’t immediately obvious, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment for many sufferers who might not associate their neck pain with digestive issues. Understanding this atypical presentation is vital for both patients and practitioners, allowing for a more holistic and effective approach to care.

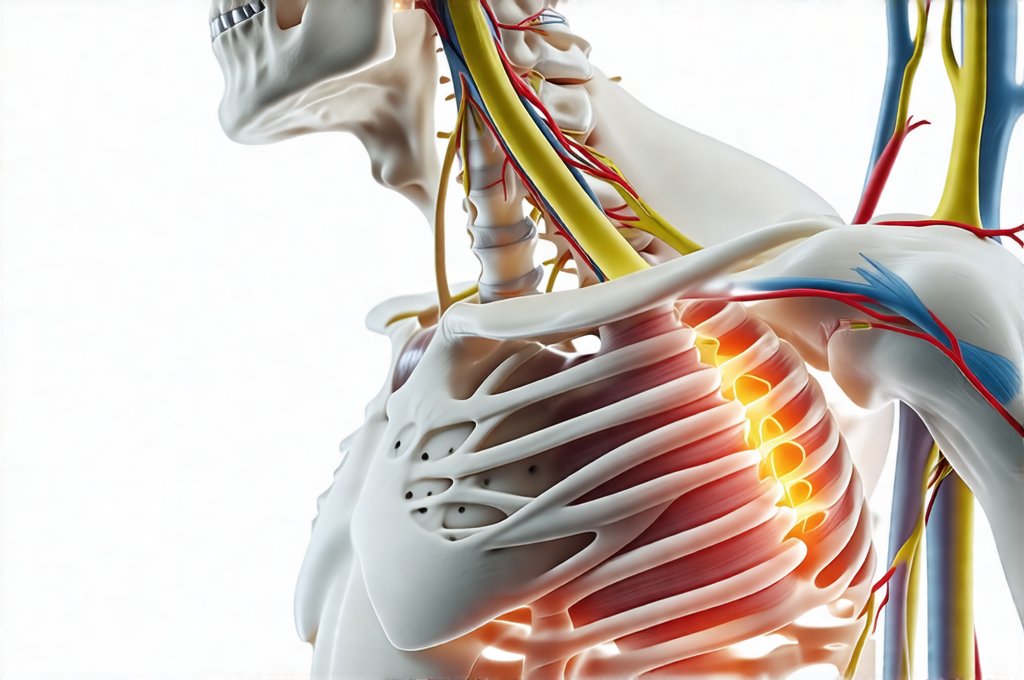

The link between GERD and neck pain stems from the complex interplay between our anatomy and physiology. The esophagus, where acid reflux originates, sits relatively close to the muscles and nerves of the neck and upper back. Furthermore, the vagus nerve – a crucial cranial nerve involved in digestion and neck muscle function – is significantly impacted by GERD symptoms. Chronic inflammation triggered by frequent acid exposure can create a cascade of effects extending beyond the digestive system, potentially leading to referred pain or musculoskeletal imbalances in the neck region. It’s important to note that this isn’t simply about stomach acid traveling up into the esophagus; it’s about the body’s response to that reflux and how those responses manifest physically. You can learn more about stomach and duodenal diseases to understand the broader context.

The Pathophysiology of GERD-Related Neck Pain

The precise mechanisms by which GERD induces neck pain are still being investigated, but several key pathways have been identified. One significant factor is esophageal dysmotility – a disruption in the normal muscular contractions that move food down the esophagus. This can lead to prolonged exposure of the esophageal lining to stomach acid and subsequent inflammation. The inflammatory response isn’t confined to the esophagus; it can trigger signals that affect surrounding structures, including those in the neck. – Chronic irritation of the vagus nerve due to GERD is thought to play a substantial role. This nerve influences not only digestive processes but also muscle tone and pain perception. – Another possibility involves referred pain patterns. Pain originating in the esophagus or diaphragm can sometimes be perceived as coming from different areas, like the neck, making diagnosis challenging. If you experience acid reflux and chest pain, it’s important to seek medical advice.

The body’s attempt to compensate for GERD can also contribute to neck pain. For example, individuals experiencing heartburn may unconsciously alter their posture – leaning forward or tightening their shoulders – to alleviate discomfort. These postural changes over time can strain neck muscles and lead to chronic tightness. Additionally, the constant irritation from acid reflux can trigger muscle guarding, where the body instinctively tenses up muscles in an attempt to protect itself, further exacerbating pain and stiffness. It’s a vicious cycle: GERD causes inflammation, leading to postural changes and muscle tension, which then amplify the discomfort and potentially worsen GERD symptoms. Understanding GERD with esophagitis can help you identify potential triggers.

This connection is particularly relevant because many people don’t experience “typical” GERD symptoms like heartburn. They may primarily feel chest pain, difficulty swallowing, or – as in this case – neck pain, making it difficult to recognize the underlying digestive issue. This underscores the importance of considering a broader differential diagnosis when evaluating neck pain and exploring potential connections to seemingly unrelated conditions.

Understanding Referred Pain & Muscle Spasms

Referred pain is a phenomenon where pain is felt in an area different from its actual source. It happens because nerves share pathways, and the brain can sometimes misinterpret the origin of the signal. In the context of GERD, irritation in the esophagus or diaphragm can send signals along nerve fibers that are also connected to neck muscles. This leads to the perception of pain localized in the neck, even though the root cause lies elsewhere. Identifying referred pain requires a thorough assessment by a healthcare professional. – They will look for patterns that don’t quite align with typical musculoskeletal issues. – They might perform specific movements or palpate different areas to try and pinpoint the source of the discomfort. It’s helpful to consider dinner meals designed for those with digestive sensitivities.

Muscle spasms are another common consequence of GERD, contributing significantly to neck pain. When the body experiences chronic irritation from acid reflux, it can trigger a protective response involving muscle tension and guarding. This leads to involuntary contractions – spasms – in the neck muscles, causing stiffness, limited range of motion, and acute pain. These spasms aren’t necessarily a direct result of physical strain; they are often a symptom of the body’s attempt to cope with underlying inflammation and discomfort. – Treating muscle spasms alone (e.g., with muscle relaxants) might provide temporary relief but won’t address the root cause – GERD.

A key aspect in differentiating GERD-related neck pain from other causes is its relationship to meals and acid reflux episodes. Often, patients will notice a worsening of their neck pain after eating certain foods or when lying down, which are common triggers for GERD. Recognizing these patterns can provide valuable clues for diagnosis and treatment.

The Role of the Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve is often called the “wandering nerve” because it extends from the brainstem to many organs throughout the body, including the esophagus, stomach, and neck muscles. It plays a critical role in regulating digestion, heart rate, breathing, and even mood. In GERD, chronic acid exposure can irritate the vagus nerve, leading to dysfunction and contributing to both digestive symptoms and musculoskeletal pain. – Vagal nerve irritation can disrupt the normal signaling between the brain and body, affecting muscle tone and potentially triggering pain signals in the neck region.

The vagus nerve also influences the diaphragm – the primary muscle involved in breathing. GERD can cause diaphragmatic dysfunction, leading to shallow breathing patterns and increased tension in the neck muscles as the body attempts to compensate for reduced respiratory efficiency. This creates a feedback loop: GERD affects the vagus nerve, which impacts the diaphragm, resulting in neck muscle strain and potentially worsening GERD symptoms. – Techniques like diaphragmatic breathing exercises can help restore proper function and reduce neck pain. If hiccups accompany your GERD, explore the connection between GERD and hiccups.

Furthermore, the vagus nerve is intimately connected to the parasympathetic nervous system – often referred to as the “rest and digest” system. When the vagus nerve is compromised by GERD, it can disrupt this balance, leading to increased stress responses and heightened sensitivity to pain. This explains why some individuals with GERD experience chronic pain syndromes that are difficult to manage.

Diagnostic Challenges & Management Strategies

Diagnosing GERD-related neck pain can be challenging because the symptoms overlap with many other conditions. A thorough medical history is crucial, focusing on digestive symptoms – even subtle ones – alongside neck pain characteristics. – Doctors may use diagnostic tests like endoscopy (to visualize the esophagus) and esophageal manometry (to assess esophageal function) to confirm GERD. – Imaging studies such as X-rays or MRI might be used to rule out other causes of neck pain, like cervical spine issues.

Management typically involves a multi-faceted approach targeting both the GERD and the musculoskeletal symptoms. This may include: 1. Lifestyle modifications: Dietary changes (avoiding trigger foods), elevating the head of the bed, losing weight if necessary, and quitting smoking. 2. Medications: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 receptor antagonists to reduce stomach acid production. 3. Physical therapy: To address muscle imbalances, improve posture, and restore range of motion in the neck. 4. Stress management techniques: Such as yoga, meditation, or deep breathing exercises, to regulate the vagus nerve and reduce overall tension.

It’s important to remember that self-diagnosing is never advisable. If you suspect a link between your GERD and neck pain, consult with a healthcare professional for an accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment plan. Ignoring the issue can lead to chronic pain, functional limitations, and reduced quality of life. A proactive approach – combining medical intervention with lifestyle changes – offers the best chance for long-term relief. You may also want to consider creating a kid-friendly food journal to track potential triggers.