Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is a minimally invasive diagnostic procedure used to collect cells from suspicious areas within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract for microscopic examination. It’s an invaluable tool in gastroenterology, helping physicians determine whether lumps or abnormalities are benign or cancerous, guiding treatment decisions, and ultimately improving patient outcomes. FNA can be performed during endoscopic procedures such as endoscopy, colonoscopy, or EUS (Endoscopic Ultrasound), or even image-guided percutaneously, offering a relatively quick and safe method for tissue sampling compared to surgical biopsies. This article provides a comprehensive overview of FNA in GI diagnostics, covering its purpose, preparation, procedure, results interpretation, potential risks, and key takeaways.

Unveiling the Potential: Understanding Fine-Needle Aspiration in GI Diagnostics

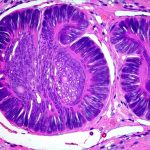

Fine-needle aspiration is essentially a technique for obtaining cells directly from suspicious tissues or lesions within the digestive system. Unlike traditional biopsies, which require larger tissue samples, FNA uses a very thin needle – often just slightly wider than a human hair – to extract a small number of cells. These cells are then examined under a microscope by a cytopathologist who can identify abnormalities and determine the nature of the growth. The procedure is frequently used in conjunction with imaging modalities like ultrasound or CT scans to ensure accurate targeting of suspicious areas and improve diagnostic accuracy. FNA allows for rapid on-site evaluation (Rapid On-Site Evaluation, or ROSE) during endoscopic procedures, which means a preliminary assessment can be made immediately during the investigation, potentially influencing further sampling decisions during the same procedure.

Why It’s Done: Conditions That Require This Test

FNA in GI diagnostics is primarily used to investigate suspicious masses or abnormalities detected during imaging studies or endoscopic examinations. Several conditions necessitate its use. One common application is evaluating lymph nodes that appear enlarged or abnormal on CT scans, as this can indicate infection, inflammation, or cancer spread. FNA also plays a crucial role in diagnosing pancreatic cysts, determining whether they are benign or have malignant potential. Furthermore, it’s used to assess suspicious lesions found during colonoscopy (such as polyps or masses) and endoscopy (in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum).

Specifically, FNA can help diagnose:

* Gastrointestinal cancers: Such as esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, and colorectal cancer.

* Lymphomas: Cancers that affect the lymphatic system.

* Inflammatory conditions: Like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, where it helps differentiate inflammation from malignancy.

* Benign tumors & cysts: Assessing whether growths are non-cancerous and don’t require aggressive treatment.

* Metastatic cancer: Determining if cancer has spread to the GI tract from another part of the body.

The goal is always to obtain sufficient cellular material for accurate diagnosis, minimizing patient discomfort and avoiding more invasive procedures when possible.

How to Prepare: Pre-Test Checklist

Preparation for FNA varies depending on how and where the procedure will be performed (endoscopic vs. image guided). For FNA done during endoscopy or colonoscopy, the preparation is largely the same as that required for those procedures. This typically involves a period of bowel preparation – including clear liquid diet and laxatives – to completely empty the digestive tract, ensuring optimal visualization. Patients are usually instructed to stop taking certain medications like blood thinners several days before the procedure, and fasting for at least six hours beforehand is standard practice.

If FNA is performed as part of an EUS procedure, similar fasting guidelines apply. For image-guided percutaneous FNA (less common in routine GI diagnostics), patients may need to refrain from eating or drinking for a specified period prior to the examination, and specific instructions regarding medication management will be provided by their healthcare team. It’s extremely important to inform your doctor about any allergies you have, especially to local anesthetics or contrast dyes, as well as any pre-existing medical conditions like heart disease or diabetes. A complete medical history is vital for ensuring patient safety during the procedure.

What to Expect During the Test: The Process Explained

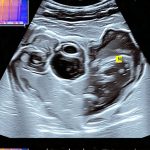

The FNA procedure itself is relatively quick and generally well-tolerated. If performed endoscopically, it occurs during the endoscopy or colonoscopy. After appropriate sedation (if indicated) and positioning, the physician will guide the endoscope to the area of concern. Using ultrasound guidance during EUS ensures precise needle placement. A very thin needle is then passed through the scope or directly through the abdominal wall (in percutaneous FNA) into the suspicious area.

The patient may feel a brief, mild pressure or discomfort as the needle enters the tissue, but it’s typically not painful due to local anesthesia applied beforehand. Several samples are usually taken from different angles within the target lesion to maximize diagnostic yield. During EUS-guided FNA, real-time imaging allows for accurate targeting and visualization of the needle’s position. The collected cell samples are then sent to a laboratory for microscopic examination by a cytopathologist. Rapid On-Site Evaluation (ROSE) can provide immediate results during the procedure itself, enabling the physician to collect additional samples if needed.

Understanding the Results: Interpreting What It Means

The interpretation of FNA results requires careful evaluation by a pathologist. The cells collected are examined under a microscope to identify any abnormalities, such as cancerous cells or signs of inflammation. Results are typically reported as either benign, malignant, inconclusive, or suspicious.

- Benign: Indicates the cells appear normal and do not suggest cancer.

- Malignant: Confirms the presence of cancer, identifying the type and grade of cancer if possible.

- Inconclusive: Means the sample did not contain enough cells for a definitive diagnosis, or that the cellular characteristics are unclear. In this case, another FNA or biopsy might be necessary.

- Suspicious: Suggests there may be cancerous changes but further investigation is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

It’s crucial to understand that an inconclusive result doesn’t necessarily mean cancer isn’t present; it simply means more information is required. Follow-up testing, such as a surgical biopsy or repeat FNA, might be recommended depending on the clinical situation and initial findings. The pathologist’s report will also provide details about any specific features of the cells observed, which can help guide treatment decisions.

Is It Safe?: Risks and Side Effects

FNA is generally considered a safe procedure, but like all medical interventions, it carries some potential risks. These are typically minor and uncommon.

- Bleeding: Mild bleeding from the puncture site is possible, but usually stops on its own.

- Infection: Infection is rare, especially with proper sterile techniques.

- Pain or discomfort: Some patients may experience mild pain or discomfort during or after the procedure, which can be managed with over-the-counter pain relievers.

- Damage to surrounding structures: Though extremely rare, there’s a small risk of damaging nearby organs or blood vessels (more likely with percutaneous FNA).

- False negative results: In some cases, the sample may not contain enough cancerous cells leading to a false negative result.

Serious complications are very uncommon and usually only occur in specific circumstances. Patients should immediately report any signs of infection (fever, redness, swelling) or excessive bleeding to their healthcare provider.

Final Thoughts: Quick Recap

FNA is a powerful diagnostic tool for evaluating suspicious areas within the gastrointestinal tract. Its minimally invasive nature, coupled with its ability to provide rapid and accurate results, makes it an invaluable asset in gastroenterology. From diagnosing cancers to assessing inflammatory conditions, FNA helps physicians make informed decisions about patient care. While risks are minimal, understanding potential complications is essential for ensuring a safe and successful procedure. Remember that open communication with your healthcare team and careful adherence to pre- and post-procedure instructions are key to achieving the best possible outcome.

Have you had an EUS or GI endoscopy with FNA? Leave a comment below to share your experience, ask questions, or help others understand this important diagnostic process.