Gastrointestinal (GI) distress is incredibly common, affecting millions globally. Symptoms ranging from bloating and abdominal pain to changes in bowel habits can significantly impact quality of life. Often, initial management involves lifestyle adjustments like dietary modifications and over-the-counter remedies. However, when symptoms persist or are severe, investigating the underlying cause becomes crucial before initiating potentially long-term medication. This is where digestive diagnostics play a vital role – they aren’t about finding disease necessarily, but about understanding what’s happening within the digestive system to guide appropriate and effective treatment plans. A thorough diagnostic approach can differentiate between functional disorders like Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and organic diseases such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), preventing unnecessary medication or, more importantly, delayed diagnosis of a serious condition. Understanding recognizing signs is the first step.

The process isn’t always straightforward. Digestive symptoms are notoriously non-specific; many conditions share similar presentations. This means relying solely on symptom reporting is often insufficient. Furthermore, the GI tract is complex and interconnected – problems in one area can manifest as symptoms elsewhere. Diagnostics aim to pinpoint the source of discomfort, assess the extent of any damage or dysfunction, and rule out serious pathology before committing to a medication regimen that might mask symptoms without addressing the root cause. This careful evaluation ensures patients receive targeted therapy based on evidence, leading to better outcomes and improved well-being. A good starting point can be found in meal timelines.

Initial Assessment & Non-Invasive Testing

The first step in digestive diagnostics typically involves a detailed medical history and physical examination. This isn’t just about listing symptoms; it’s about understanding the context of those symptoms – when they started, what makes them better or worse, family history of GI diseases, medications taken, dietary habits, stress levels, and any associated systemic symptoms like fatigue or weight loss. This initial assessment often guides the selection of subsequent tests. Non-invasive testing forms the cornerstone of many investigations, providing a wealth of information without requiring procedures that carry significant risk or discomfort.

These non-invasive methods are frequently employed as first-line tools. For example, stool analysis can identify infections (bacterial, parasitic), malabsorption issues (indicated by fat content), and signs of inflammation. Blood tests assess for anemia (suggesting bleeding in the GI tract), inflammatory markers (elevated in IBD or infection), liver function, pancreatic enzymes, and celiac disease antibodies. Breath tests are particularly useful for diagnosing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) or lactose intolerance by measuring hydrogen gas production after consuming specific substrates. These initial investigations help narrow down potential diagnoses and determine if more advanced testing is needed. Consider prep-ahead meals to aid in tracking responses to food.

A crucial part of this stage is often dietary modification, sometimes as a diagnostic tool in itself. For instance, a trial elimination diet might be used to identify food sensitivities or intolerances contributing to symptoms. The goal isn’t necessarily long-term restriction but rather gathering information about how the digestive system responds to different foods. It’s important to note that these initial tests aren’t always conclusive; negative results don’t automatically rule out a problem, and further investigation may still be required. The focus is on building a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s individual situation. Daily eating maps can provide structure during this process.

Endoscopic Procedures: Visualizing the GI Tract

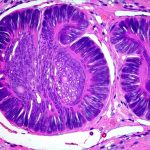

When non-invasive testing doesn’t provide enough clarity, endoscopic procedures become invaluable. These involve inserting a flexible tube with a camera attached into the digestive tract to directly visualize its lining. Upper endoscopy (also known as esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD) examines the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. It’s particularly useful for investigating symptoms like heartburn, difficulty swallowing, abdominal pain, and bleeding. During an upper endoscopy, biopsies can be taken to check for inflammation, ulcers, infection (like Helicobacter pylori), or cancer.

Colonoscopy, on the other hand, examines the entire colon and rectum. It’s a critical tool in screening for colorectal cancer, identifying polyps (which are precancerous growths), and investigating symptoms like changes in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, and abdominal pain. Like upper endoscopy, biopsies can be taken during colonoscopy to assess for inflammation or other abnormalities. Preparation for these procedures typically involves dietary restrictions and bowel preparation (for colonoscopy) to ensure clear visualization. While endoscopic procedures are generally safe, they do carry some risks, such as perforation (rarely), bleeding, and infection.

The information gained from endoscopy is often decisive in determining the appropriate course of action. It allows doctors to differentiate between benign conditions like gastritis and more serious ones like ulcers or cancer, leading to targeted treatment strategies. Furthermore, endoscopic procedures can sometimes be therapeutic; for example, polyps can be removed during colonoscopy, preventing them from developing into cancer. Comfort-based routines can help prepare patients mentally for these procedures.

Imaging Techniques: A Deeper Look Inside

Beyond endoscopy, various imaging techniques provide valuable diagnostic information. Abdominal X-rays are often used as a first step to identify blockages or perforations, but their resolution is limited for detailed assessment of soft tissues. Computed Tomography (CT) scans offer much greater detail and can reveal abnormalities in the organs, blood vessels, and bones within the abdomen. They’re useful for diagnosing conditions like appendicitis, diverticulitis, and tumors. However, CT scans involve exposure to radiation, so their use is generally reserved for cases where more detailed information is needed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides excellent soft tissue detail without using ionizing radiation. It’s particularly helpful in evaluating the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, and bowel, and can be used to detect inflammation, tumors, and other abnormalities. A specialized MRI called Magnetic Resonance Enterography (MRE) focuses specifically on the small intestine, which is often difficult to visualize with other imaging techniques – making it useful for diagnosing Crohn’s disease.

Finally, ultrasound uses sound waves to create images of the abdominal organs. It’s non-invasive and relatively inexpensive, but its resolution isn’t as high as CT or MRI. It’s commonly used to evaluate the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas, and can help identify gallstones or other abnormalities. The choice of imaging technique depends on the specific symptoms and suspected diagnosis. Doctors carefully weigh the benefits and risks of each method before recommending it to a patient. One-dish meals can be easier on the digestive system while awaiting test results.

This thorough diagnostic process, starting with non-invasive tests and progressing to more advanced procedures if needed, is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of digestive disorders. It’s about empowering patients and healthcare providers with the information necessary to make informed decisions and optimize care.