The modern Western diet often lacks sufficient fiber, leading many people to experience digestive discomfort when they attempt to significantly increase their intake. This initial reaction—bloating, gas, even changes in bowel habits—can be discouraging, prompting some to abandon efforts to boost fiber consumption altogether. However, the human body is remarkably adaptable. The question isn’t if your body can adapt to more fiber, but rather how it adapts and what steps you can take to facilitate a smoother transition. Understanding this adaptive process is crucial for reaping the many health benefits associated with a fiber-rich diet – from improved gut health and weight management to reduced risk of chronic diseases.

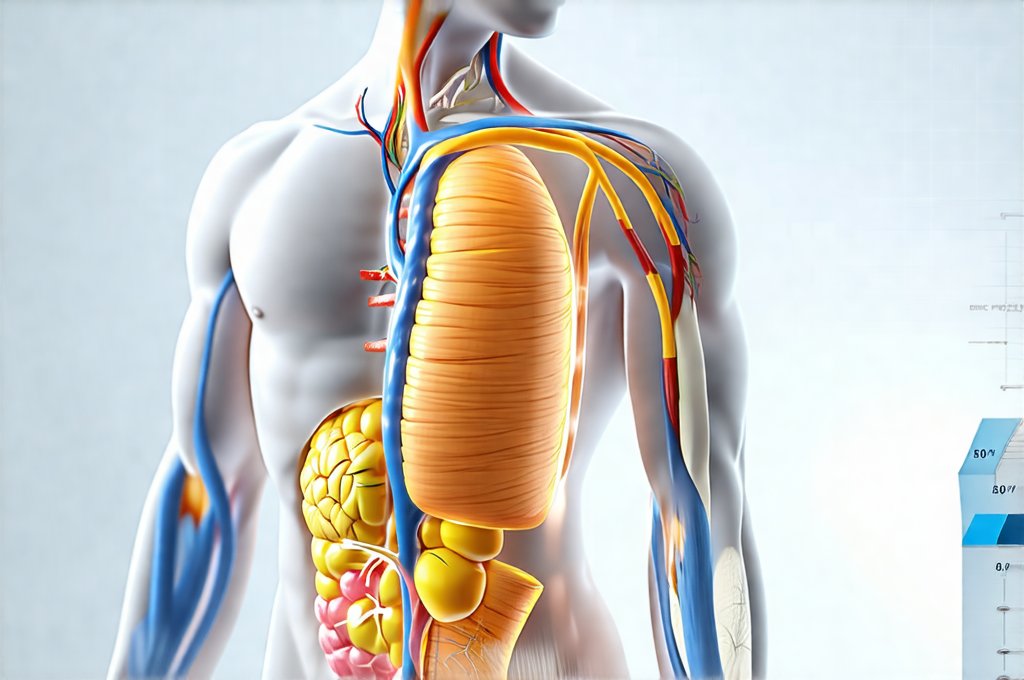

Fiber isn’t digested by our bodies like other carbohydrates, proteins, or fats; instead, it passes relatively intact through the digestive system. This seemingly simple fact explains why sudden increases in fiber can cause issues. Our gut microbiome—the vast community of bacteria residing in our intestines—plays a pivotal role in how we process fiber. These microbes ferment fiber, breaking it down into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that nourish the gut lining and provide numerous health benefits. But if your diet has historically been low in fiber, the population of fiber-digesting bacteria may be limited, leading to undigested fiber reaching the large intestine and causing discomfort. Over time, with consistent fiber intake, this microbial community can shift and grow, becoming more efficient at processing fiber and minimizing these initial side effects. You might even find can your gut adapts over time.

The Gut Microbiome & Fiber Adaptation

The gut microbiome is truly a dynamic ecosystem, responding directly to dietary changes. It’s not just about adding more fiber; it’s about feeding the right kinds of bacteria. Different types of fiber—soluble versus insoluble, from various food sources—support different microbial populations. Soluble fiber, found in oats, beans, and apples, dissolves in water forming a gel-like substance, slowing digestion. Insoluble fiber, prevalent in whole grains and vegetables, adds bulk to the stool and aids regularity. Both are essential, but their impact on the microbiome differs. When you increase fiber intake, you’re essentially providing food for these microbes, encouraging growth and diversification. If digestive issues are impacting your ability to be active, consider gerd can reduce how this might affect you.

This process isn’t immediate. It takes time – often weeks or even months – for significant changes in microbial composition to occur. Think of it like cultivating a garden; you can’t expect instant blooms after planting seeds. The speed of adaptation is also influenced by individual factors such as genetics, existing gut health, and overall diet quality. Someone with a pre-existing healthy microbiome may adapt more quickly than someone whose gut flora has been significantly disrupted by antibiotics or a highly processed food diet. A diverse microbial community is generally considered a sign of a healthy gut, capable of efficiently processing a wider range of fiber types.

Crucially, consistency is key. Sporadic fiber intake won’t allow the microbiome to establish a stable population of fiber-digesting bacteria. Regular, sustained consumption is necessary for lasting adaptation and benefit. Furthermore, focusing on whole food sources of fiber—fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains—provides additional nutrients that support overall gut health and microbial diversity. It’s important to build trust with your body during this process.

Mechanisms of Fiber Adaptation

The body adapts to increased fiber intake through several interconnected mechanisms beyond just changes in the microbiome. One key aspect is an increase in colonic motility – the movement of muscles within the colon. Initially, undigested fiber can slow things down, causing bloating. However, as the gut microbiome becomes more efficient at fermentation and SCFAs are produced, these compounds stimulate colonic contractions, enhancing motility and helping move waste through the digestive system.

- This improved motility reduces the time fiber spends in the large intestine, minimizing discomfort.

- Simultaneously, the intestinal lining adapts by increasing mucus production. Mucus acts as a lubricant, easing the passage of stool and protecting the gut wall from irritation.

- Another important adaptation involves changes in enzyme production within the digestive system. Although we don’t digest fiber ourselves, our bodies can adjust to better handle its presence, reducing inflammation and improving nutrient absorption.

These adaptations aren’t solely confined to the digestive tract either. The SCFAs produced by microbial fermentation have systemic effects, impacting immune function, metabolism, and even brain health. This highlights the profound interconnectedness between gut health and overall wellbeing. A healthy, fiber-adapted gut isn’t just about comfortable digestion; it’s an integral part of a thriving body. In some instances, gerd can impact overall wellbeing too.

Gradual Increase & Hydration is Essential

The most common mistake when increasing fiber intake is doing too much too soon. This overwhelms the digestive system and leads to unpleasant side effects, often causing people to give up. A gradual approach is far more effective. Start by adding small amounts of fiber-rich foods to your diet – perhaps a handful of berries with breakfast or a serving of lentils at lunch. Then, slowly increase the amount over several weeks, paying attention to how your body responds.

- Begin with 5-10 grams of additional fiber per day.

- Monitor for any digestive discomfort. If you experience bloating or gas, reduce intake slightly and allow your gut to adjust before increasing again.

- Gradually increase by 2-3 grams every few days until you reach your desired level – typically around 25-35 grams per day.

Hydration is absolutely crucial. Fiber absorbs water, so if you’re not drinking enough fluids, the increased fiber can actually worsen constipation and discomfort. Aim to drink at least eight glasses of water daily, and even more if you’re physically active or live in a hot climate. Consider spreading your fluid intake throughout the day rather than consuming large amounts at once. Understanding how your body reacts to dietary changes is key.

Identifying Fiber Sensitivity & Potential Issues

While most people can adapt to increased fiber, some individuals may experience persistent sensitivity despite gradual increases. This could be due to underlying conditions such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) or Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). In these cases, certain types of fiber—particularly FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols)—can exacerbate symptoms. FODMAPs are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine, leading to fermentation in the large intestine and causing gas, bloating, and abdominal pain.

If you suspect fiber sensitivity or have an underlying digestive condition, it’s important to work with a registered dietitian or healthcare professional. They can help identify trigger foods, develop a personalized dietary plan, and rule out any other potential causes of your symptoms. It’s also vital to remember that “more” isn’t always better. Focusing on quality over quantity – prioritizing whole food sources of fiber and paying attention to individual tolerance levels – is the most effective approach. A carefully planned strategy allows you to reap the benefits of fiber without compromising digestive comfort or overall wellbeing. You may even react differently over time.