The human gut is an incredibly complex ecosystem, teeming with trillions of microorganisms and playing a pivotal role in overall health. Beyond simply digesting food, the gut influences immune function, mental wellbeing, and even chronic disease risk. Traditionally, assessing nutritional status relied heavily on blood tests, dietary recall, and physical examinations. However, these methods often provide snapshots in time and may not accurately reflect long-term vitamin absorption or utilization. Increasingly, scientists are recognizing the potential of stool analysis as a non-invasive way to gain deeper insights into gut health and identify subtle vitamin deficiencies before they manifest as overt symptoms. This shift is driven by the understanding that many vitamins are either not fully absorbed from food, altered by gut bacteria, or excreted in feces, offering valuable biomarkers within the stool matrix.

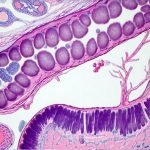

The promise of stool-based diagnostics for vitamin assessment lies in its ability to integrate information about both dietary intake and intestinal function. Blood tests measure what’s circulating in the bloodstream at a particular moment, but they don’t necessarily reflect what’s happening within the gut itself – where much of vitamin absorption and metabolism occurs. Stool samples, on the other hand, provide a more holistic picture by capturing vitamins that weren’t absorbed, metabolites produced by gut bacteria (which can indicate utilization), and even unabsorbed dietary components. This approach is particularly useful for fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) which rely heavily on efficient digestion and absorption, as deficiencies can easily go undetected with standard blood tests due to their transport mechanisms. The field is still evolving, but the potential for personalized nutrition interventions based on stool analysis is significant. Understanding hidden signs can be crucial in this process.

Vitamin Absorption & Stool Biomarkers

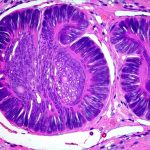

The process of vitamin absorption isn’t straightforward. It’s influenced by a multitude of factors including age, genetics, gut microbiome composition, and overall health status. When vitamins aren’t fully absorbed, they pass into the large intestine where they can be modified by bacterial activity or simply excreted. This presents an opportunity to detect deficiencies through stool analysis. Several key vitamin-related biomarkers can be assessed in a stool sample:

- Vitamin Concentration: Directly measuring vitamin levels (e.g., Vitamin D3, Vitamin B12) in the stool indicates how much of the ingested vitamin wasn’t absorbed. Low concentrations may suggest malabsorption issues.

- Metabolite Analysis: Analyzing metabolites provides insight into how vitamins are being used by the body and gut bacteria. For example, assessing certain indole compounds can reflect Vitamin B metabolism.

- Fat Content & Elastase: Since fat-soluble vitamin absorption is reliant on healthy fat digestion, stool fat content serves as an indicator of overall digestive efficiency. Pancreatic elastase levels also indicate pancreatic function which is crucial for proper fat (and therefore fat-soluble vitamin) digestion.

- Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): While not directly a vitamin biomarker, SCFAs produced by gut bacteria are heavily influenced by dietary fiber and indirectly impact vitamin absorption and overall gut health.

The complexity of the gut microbiome adds another layer to this assessment. Gut bacteria can both enhance and inhibit vitamin absorption. Some bacteria synthesize vitamins (like Vitamin K and some B vitamins) while others degrade them. Understanding the composition of the microbiome alongside vitamin levels provides a more nuanced understanding of nutritional status. This is why comprehensive stool tests often include 16S rRNA sequencing or metagenomic analysis to identify bacterial populations. It’s important to understand how stress wrecks digestion and impacts vitamin absorption.

Limitations & Future Directions

Despite its promise, stool-based diagnostics for vitamin assessment are not without limitations. One significant challenge is standardization. There’s currently a lack of universally accepted protocols for sample collection, processing, and interpretation. Different labs use different methods, making it difficult to compare results across studies or institutions. Furthermore, the influence of diet on stool vitamin levels can be substantial, requiring careful consideration during interpretation. A person who recently consumed a large amount of Vitamin C-rich foods will naturally have higher levels in their stool, potentially masking an underlying deficiency. It is also important to consider diagnostics that reveal why gut symptoms happen as a potential cause for altered absorption.

Another limitation is that stool analysis primarily reflects unabsorbed vitamins – it doesn’t necessarily provide information about tissue stores or functional vitamin status within the body. While low stool levels might indicate malabsorption, they don’t confirm a clinical deficiency without corroborating evidence from other sources. Research is ongoing to refine these techniques and develop more reliable biomarkers. This includes exploring new analytical methods like mass spectrometry for enhanced sensitivity and accuracy, as well as developing algorithms that account for dietary factors and individual microbiome profiles. The future of vitamin assessment may involve integrating stool analysis with blood tests, genetic testing, and personalized diet plans to create a truly comprehensive understanding of an individual’s nutritional needs. GI checkups can help understand the broader context.

Vitamin D & Stool Analysis

Vitamin D deficiency is remarkably prevalent worldwide, often going unnoticed due to its subtle initial symptoms. Traditional assessment relies on measuring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], but this doesn’t fully capture the complexities of Vitamin D metabolism and absorption. Stool analysis can offer complementary information by assessing unabsorbed Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) levels. This is particularly valuable for individuals with conditions affecting fat absorption, such as Crohn’s disease, Celiac disease, or cystic fibrosis, where conventional blood tests may not accurately reflect the deficiency.

- Low stool Vitamin D3 concentrations can indicate insufficient dietary intake, impaired absorption due to digestive issues, or inadequate conversion of Vitamin D2/D3 within the gut.

- Analyzing fecal fat content alongside Vitamin D levels provides a more complete picture of fat malabsorption and its impact on vitamin status.

- Emerging research is exploring the role of gut bacteria in influencing Vitamin D metabolism and absorption, potentially leading to novel stool biomarkers related to microbial activity.

Furthermore, assessing Vitamin D metabolites within the stool – though technically challenging – could provide insights into how effectively the body is utilizing ingested or synthesized Vitamin D. It’s important to remember that stool analysis isn’t a replacement for blood tests but rather a valuable adjunct to help identify individuals at risk of deficiency and tailor interventions accordingly.

B Vitamins & The Gut Microbiome

B vitamins are crucial for numerous metabolic processes, and deficiencies can have widespread health consequences. Unlike fat-soluble vitamins, many B vitamins are water-soluble and readily excreted in urine, making blood tests less reliable indicators of overall status. Stool analysis offers a unique perspective on B vitamin metabolism by assessing both unabsorbed vitamins and metabolites produced by gut bacteria.

- Certain gut bacteria synthesize Vitamin K and some B vitamins (like folate), contributing to the body’s overall supply.

- Stool metabolite analysis can identify specific bacterial pathways involved in B vitamin production or degradation, providing insights into microbiome function.

- Assessing unabsorbed Vitamin B12 levels can help detect malabsorption issues related to intrinsic factor deficiency (common in pernicious anemia) or intestinal dysbiosis.

The gut microbiome plays a complex role in B vitamin metabolism, and imbalances in bacterial populations can contribute to deficiencies. For example, an overgrowth of certain bacteria can lead to increased degradation of Vitamin B12, while a lack of beneficial bacteria may reduce the synthesis of other essential B vitamins. Comprehensive stool testing that includes microbiome analysis alongside B vitamin levels is crucial for understanding these interactions. Low-cost diagnostics can provide initial insights into gut health.

Assessing Folate & Iron Status Through Stool

Folate (Vitamin B9) is vital for DNA synthesis and cell growth, with deficiencies linked to neural tube defects during pregnancy and anemia. While blood tests measure folate levels, they don’t necessarily reflect the amount available for cellular use. Similarly, iron deficiency is a common nutritional concern, but assessing iron status solely through serum ferritin can be misleading due to inflammation or acute phase responses. Stool analysis offers alternative ways to evaluate these nutrients:

- Stool folate levels can indicate dietary intake and absorption efficiency, particularly useful in identifying individuals with malabsorption syndromes.

- Fecal calprotectin – a marker of intestinal inflammation – can indirectly impact iron absorption, making it a relevant biomarker when assessing iron status alongside stool iron levels.

- Assessing fecal hemoglobin (fHb) is primarily used to detect gastrointestinal bleeding, but chronic blood loss can deplete iron stores and contribute to anemia; therefore, its measurement in stool is connected to iron assessment.

The gut microbiome also influences folate metabolism. Some bacteria produce folate while others consume it, impacting the overall availability of this essential nutrient. Analyzing bacterial populations alongside stool folate levels provides a more nuanced understanding of folate status. It’s crucial to remember that these assessments are best interpreted within the context of an individual’s medical history, diet, and other relevant factors. If you notice weird reactions to food, consider diagnostics that explain weird reactions.