Upper abdominal pain is a remarkably common complaint, presenting clinicians with a diagnostic challenge due to the vast array of potential causes ranging from relatively benign conditions like gastritis to serious life-threatening emergencies such as aortic dissection or myocardial infarction referred pain. Accurately identifying the source requires a systematic approach that considers the patient’s history, performs a thorough physical examination, and judiciously selects appropriate diagnostic tests. The complexity arises not only from the sheer number of possible diagnoses but also because many conditions can present with similar symptoms, making differentiation crucial for timely and effective management. Failing to pinpoint the underlying cause can lead to delayed treatment, increased morbidity, and unnecessary interventions.

The goal isn’t simply to name the problem; it’s to understand its nature—is this an acute versus chronic issue? Is there evidence of inflammation, obstruction, or vascular compromise? The selection of tests must be guided by the initial clinical assessment, prioritizing those that offer the highest yield based on the suspected pathology. Over-testing should be avoided, as it increases costs, can lead to false positives and unnecessary anxiety for the patient, and potentially delays appropriate care if results are misinterpreted or overshadowed by incidental findings. A thoughtful, stepwise approach is key to navigating this diagnostic landscape.

Initial Assessment & Basic Investigations

The first step in evaluating upper abdominal pain is a detailed history and physical examination. This should include questions about the onset, location, duration, character, aggravating and alleviating factors, and associated symptoms like nausea, vomiting, fever, or changes in bowel habits. A family history of gastrointestinal disorders, medication use (including over-the-counter drugs), and social habits such as alcohol consumption and smoking are also important to gather. The physical exam should focus on abdominal palpation, auscultation for bowel sounds, and percussion to assess for tenderness, guarding, rebound tenderness or organomegaly. Initial investigations often begin with relatively simple and readily available tests.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): This can help identify signs of infection (elevated white blood cell count), anemia (suggesting chronic bleeding from a gastrointestinal source), or thrombocytopenia.

- Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP): Evaluates liver function, kidney function, electrolytes, and glucose levels providing crucial information about overall health and potential metabolic disturbances. Abnormalities may point toward specific organ involvement.

- Urinalysis: Helps rule out urinary tract infections or kidney stones which can sometimes present with referred pain to the upper abdomen.

- Stool tests: Depending on the clinical picture, stool studies might be indicated to evaluate for infection (e.g., C. difficile), parasites, or occult blood.

These initial investigations provide a baseline assessment and help narrow down the differential diagnosis. They can often identify common causes of upper abdominal pain, such as gastroenteritis or mild liver enzyme elevations, but further testing is frequently required when symptoms are persistent, severe, or atypical. A pragmatic approach dictates avoiding extensive testing until these initial evaluations have been completed and interpreted. Understanding are you eating the right amount can also help in diagnosis.

Imaging Modalities

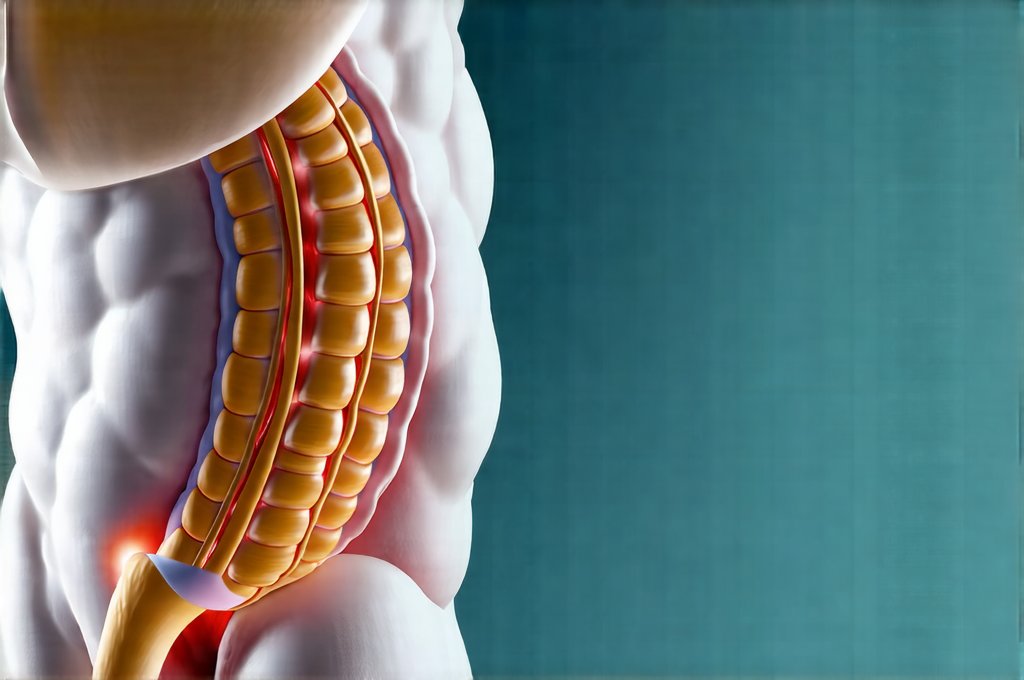

Imaging plays a crucial role in diagnosing the cause of upper abdominal pain. The choice of imaging modality depends on the suspected pathology and the clinical context. Ultrasound is often the first-line imaging study for evaluating the gallbladder, bile ducts, liver, and pancreas due to its non-invasive nature, lack of ionizing radiation, and relatively low cost. Computed Tomography (CT) scans provide more detailed anatomical information and are useful for assessing a wider range of conditions including pancreatitis, appendicitis, bowel obstruction, aortic aneurysms, and masses in the upper abdomen. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) offers excellent soft tissue detail and is often used to further evaluate findings seen on CT or ultrasound, particularly when investigating pancreatic lesions or biliary disorders.

The appropriate use of imaging requires careful consideration of the patient’s medical history, physical examination findings, and initial laboratory results. For example, a patient with suspected gallstones would likely benefit from an ultrasound, while a patient presenting with severe abdominal pain and suspected bowel obstruction might require a CT scan. It’s also essential to weigh the risks and benefits of each imaging modality, considering factors such as radiation exposure (CT scans) and cost. The principle of ‘image judiciously’ is paramount. If you experience chronic pain, consider GERD and pain as a possible cause.

Pancreatic & Biliary Investigations

If pancreatic involvement is suspected—based on symptoms like epigastric pain radiating to the back, nausea, and vomiting—specific tests become necessary.

– Amylase and Lipase: These are enzymes produced by the pancreas; elevated levels in the blood strongly suggest pancreatitis. Lipase is generally considered more specific for pancreatic injury than amylase. Serial measurements can help monitor disease progression.

– Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS): Provides detailed images of the pancreas and bile ducts, allowing for assessment of inflammation, masses, or stones. It also allows for biopsy if needed.

– Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): A non-invasive imaging technique that provides excellent visualization of the biliary system and pancreatic duct.

For suspected biliary pathology—often presenting as right upper quadrant pain radiating to the shoulder, potentially with nausea and vomiting—further investigation is crucial.

– Liver Function Tests (LFTs): Elevations in bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, or transaminases suggest liver or biliary dysfunction.

– HIDA scan: A nuclear medicine study that assesses gallbladder function and patency of the cystic duct. Useful for diagnosing acute cholecystitis.

Cardiovascular Considerations

Upper abdominal pain isn’t always gastrointestinal in origin; cardiovascular causes must be considered, particularly in patients with risk factors for heart disease. Referred pain from myocardial ischemia can sometimes mimic abdominal symptoms.

– Electrocardiogram (ECG): A standard test to evaluate heart rhythm and detect evidence of ischemia or infarction. Serial ECGs might be necessary if suspicion is high.

– Cardiac Enzymes: Troponin levels are elevated in the event of a heart attack, helping differentiate cardiac pain from other causes.

– Abdominal Aortic Ultrasound/CT Angiography: If an aortic dissection or aneurysm is suspected—often presenting with severe, tearing abdominal pain—urgent imaging is required to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment.

Gastric & Duodenal Evaluation

When symptoms suggest a gastric or duodenal ulcer or gastritis, more focused investigations are warranted.

– Endoscopy (EGD): Allows direct visualization of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, enabling identification of ulcers, inflammation, or masses. Biopsies can be taken for histological analysis and to test for Helicobacter pylori infection.

– Urea Breath Test/Stool Antigen Test: Used to diagnose H. pylori infection, a common cause of peptic ulcer disease. Eradication therapy is often prescribed if the organism is detected.

– Gastric emptying study: Assesses how quickly food empties from the stomach, helping diagnose gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying. When evaluating abdominal discomfort, when to seek medical attention is important.

The evaluation of upper abdominal pain is a complex process requiring careful consideration of multiple factors. A systematic approach that combines thorough history taking, physical examination, and judicious test selection is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management. Choosing the right digestive test can streamline this process. Remember to consider finding the right pace for eating as well. Finally, if appropriate, choosing the right probiotic supplement could be beneficial. This information is not intended as medical advice; always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns.