Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder affecting millions worldwide, characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhea, and constipation – often fluctuating in severity and presentation. Managing IBS effectively isn’t about ‘curing’ it, as there’s currently no known cure, but rather understanding the individual’s unique triggers and developing a long-term care plan to minimize symptoms and improve quality of life. This necessitates a comprehensive diagnostic approach that goes beyond simply identifying that someone has IBS, focusing instead on ruling out other conditions, determining the predominant symptom (IBS-D, IBS-C, or IBS-M), and uncovering individual sensitivities. A robust long-term care strategy relies heavily on accurate diagnosis to tailor treatment effectively.

The challenge with IBS lies in its overlapping symptoms with many other digestive disorders, making definitive diagnosis tricky. It’s often described as a ‘diagnosis of exclusion’, meaning other potential causes must be systematically ruled out before an IBS diagnosis is confidently made. Furthermore, the subjective nature of symptoms – relying heavily on patient reporting – adds another layer of complexity. Therefore, diagnostic tools aren’t just about identifying what is wrong but also about understanding why and how it affects each individual differently. This article explores the various diagnostic tools employed in long-term IBS care, from initial assessments to more specialized tests, emphasizing their role in building a personalized management plan.

Initial Assessments & Symptom Tracking

The first step in diagnosing IBS invariably involves a detailed medical history and physical examination. A healthcare professional will ask about your symptoms – their frequency, severity, duration, and any associated factors (like stress or specific foods). This includes exploring bowel habits: stool consistency (using scales like the Bristol Stool Form Scale), frequency of bowel movements, urgency, and incomplete evacuation feelings. Family history of gastrointestinal disorders is also crucial information. The physical exam itself is often relatively unremarkable in IBS patients, but it helps to rule out other potential causes and assess for signs of more serious conditions.

Beyond the initial consultation, symptom tracking plays a vital role. Keeping a detailed food diary – noting what you eat, when you eat it, and any associated symptoms – can reveal patterns and identify potential trigger foods. Similarly, logging stress levels and correlating them with symptom flare-ups helps understand the impact of psychological factors. There are numerous apps available to assist with this process, making it easier and more consistent. These logs aren’t just for diagnosis; they become invaluable tools for ongoing management, helping individuals proactively avoid triggers and monitor the effectiveness of their treatment plan. The Rome IV criteria, a globally recognized set of diagnostic criteria, is frequently used during assessment, focusing on recurrent abdominal pain associated with defecation or a change in stool frequency/form.

Finally, initial blood tests are standard practice. These aren’t specifically for IBS diagnosis (as there’s no biomarker for IBS itself) but help rule out other conditions that mimic its symptoms, such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD – Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis), and infections. Common blood tests include a complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) to assess for inflammation, thyroid function tests, and sometimes testing for Helicobacter pylori infection. These initial assessments provide a baseline and help guide further investigations if necessary. Understanding the role of nutritionists in cancer care can be helpful during this process as well.

Specialized Testing: Beyond the Basics

If initial assessment suggests IBS but other causes haven’t been definitively ruled out, or if symptoms are particularly severe or atypical, more specialized testing may be considered. This is where diagnosis becomes more nuanced. The goal isn’t necessarily to ‘find’ IBS (as it’s a functional disorder), but rather to confidently exclude other possibilities and refine the understanding of an individual patient’s presentation.

- Stool Tests: Stool tests are often used to rule out infections (bacterial, viral, or parasitic) as well as malabsorption issues. Calprotectin levels in stool can help differentiate between IBS and IBD; elevated calprotectin suggests inflammation consistent with IBD. Testing for occult blood is also common, although it’s less specific for IBS itself. Newer stool tests are emerging that analyze the gut microbiome—the community of bacteria living in your digestive tract—but their clinical utility in routine IBS diagnosis is still evolving.

- Lactose and Fructose Breath Tests: These tests assess for carbohydrate malabsorption. Lactose intolerance, for example, can cause symptoms very similar to IBS. The patient consumes a measured amount of lactose or fructose, and breath samples are analyzed for hydrogen gas production—an indicator of bacterial fermentation due to undigested carbohydrates. A positive test suggests sensitivity to that sugar.

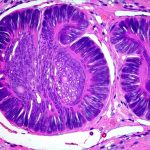

- Colonoscopy & Endoscopy: While not always necessary, these procedures are often recommended, especially in patients over 50 or those with alarm symptoms (rectal bleeding, unexplained weight loss, anemia). Colonoscopy involves inserting a flexible tube with a camera into the colon to visualize the lining and rule out conditions like polyps, cancer, or IBD. Endoscopy examines the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Biopsies can be taken during these procedures for further analysis.

Hydrogen Breath Testing & Gut Microbiome Analysis

Hydrogen breath testing (HBT) has become increasingly important in identifying specific carbohydrate intolerances beyond just lactose and fructose. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition where excessive bacteria reside in the small intestine, leading to fermentation of carbohydrates and producing hydrogen gas – which is then exhaled and detectable. HBT for SIBO involves consuming a glucose or lactulose solution, followed by breath sample collection over several hours. The pattern of hydrogen and methane (another gas produced by some gut bacteria) excretion helps determine if SIBO is present. It’s important to note that HBT results can be influenced by various factors, including diet and bowel preparation, so standardized protocols are essential.

Gut microbiome analysis – often performed using stool samples – aims to identify the composition of bacteria in your digestive tract. The gut microbiome plays a critical role in digestion, immunity, and overall health. While research is ongoing, alterations in the microbiome have been linked to IBS symptoms. Analysis can reveal imbalances (dysbiosis), lack of diversity, or overgrowth of specific bacterial strains. However, interpreting these results can be complex. There isn’t yet a ‘normal’ gut microbiome profile; it varies significantly between individuals. The clinical utility of microbiome testing is evolving, and it’s often used to guide dietary interventions like prebiotic or probiotic supplementation, but not as the sole basis for diagnosis. It’s crucial to work with a healthcare professional who can interpret these results in the context of your individual symptoms and medical history. Considering daily gut care habits for long-term digestive ease is also beneficial. Understanding the role of the vagus nerve in IBS may provide additional insights.

Ultimately, long-term IBS care relies on a holistic approach that integrates accurate diagnostic tools with personalized management strategies. By identifying triggers, understanding symptom patterns, and ruling out other conditions, individuals can take control of their health and improve their quality of life. Importance of patient advocacy in cancer care is also helpful when navigating diagnosis. Remember to always consult with a healthcare professional for any medical concerns or before making changes to your diet or treatment plan.