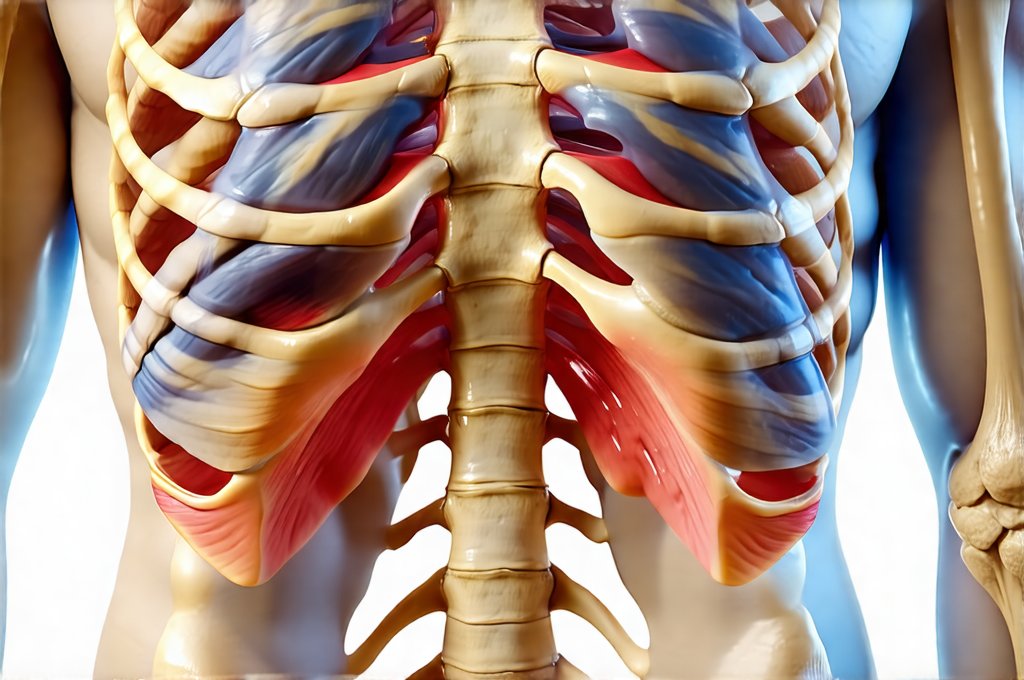

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a remarkably common condition, affecting millions worldwide. Often characterized by heartburn and acid indigestion, its impact extends far beyond these typical symptoms. Many individuals experiencing GERD unexpectedly find themselves grappling with chest pain, which can be profoundly unsettling, often leading to anxiety about potential cardiac issues. A significant reason for this confusion lies in the phenomenon of referred pain, where discomfort originating from one area of the body is perceived as coming from another. Understanding how GERD manifests as rib cage or chest pain through referred pain mechanisms is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management – not just of the GERD itself, but also the associated psychological distress it can cause.

The complexity stems from shared nerve pathways. The esophagus, stomach, and heart all share overlapping sensory innervation. This means that signals generated by irritation or inflammation in the esophagus due to acid reflux can sometimes be misinterpreted by the brain as originating from the chest wall or even the heart itself. It’s not a simple case of mistaking one for the other; it’s a neurological reality where the brain struggles to pinpoint the precise source of pain, especially when signals are ambiguous. This often leads patients to believe they are having cardiac problems, prompting emergency room visits and unnecessary worry. Differentiating between GERD-related chest pain and heart-related chest pain is therefore paramount, but requires an understanding of how these conditions present differently and a careful medical evaluation.

Understanding the Link Between GERD & Chest Pain

The connection between GERD and rib cage/chest pain isn’t about direct inflammation affecting the ribs themselves. It’s almost entirely related to referred pain – a common experience where pain is felt in an area distant from its actual origin. The esophagus, when irritated by stomach acid refluxing upwards, stimulates nerve fibers that also supply the chest wall and rib cage areas. This shared innervation creates a pathway for pain signals to be misinterpreted. Imagine it like a crossed wire; the brain receives a signal but attributes it to the wrong location. This can manifest as a burning sensation, tightness, or even sharp stabbing pains in the chest, mimicking musculoskeletal discomfort.

The type of GERD also plays a role. Mild, infrequent heartburn might not cause significant referred pain. However, more severe cases – including those with complications like esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus) or strictures (narrowing of the esophagus) – are far more likely to generate stronger pain signals that trigger this referral pattern. Furthermore, the position and severity of acid reflux can influence where in the chest the pain is felt. Reflux reaching higher into the esophagus tends to produce pain closer to the sternum (breastbone), while lower esophageal involvement might feel more like abdominal discomfort radiating upwards.

It’s important to note that not everyone with GERD will experience chest pain, and not all chest pain is caused by GERD. The interplay between individual sensitivity to pain, the severity of reflux, and the specific neurological pathways involved determines whether or not referred pain occurs. This highlights the need for a thorough medical evaluation to rule out other potential causes. Understanding common causes can help with this process.

Distinguishing GERD-Related Pain from Cardiac Pain

Accurately differentiating between GERD-related chest pain and cardiac pain (angina) is critical, as the latter requires immediate attention. While both can present with similar symptoms – tightness, pressure, or discomfort in the chest – several key differences often exist. Cardiac pain is typically described as a crushing, squeezing sensation that may radiate to the left arm, jaw, neck, or back. It’s often brought on by exertion and relieved by rest. GERD-related pain, conversely, is more likely to be burning in nature, worsen after eating, bending over, or lying down, and might be relieved by antacids.

However, these are generalizations, and overlap can occur. A helpful approach involves considering the context of the pain. Ask yourself:

1. Does the pain change with physical activity?

2. Is it accompanied by shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, or dizziness? (These are more common in cardiac events.)

3. Do antacids provide relief?

- If you suspect cardiac pain, seek immediate medical attention. Do not attempt to self-diagnose.

- If the pain is clearly related to eating and relieved by antacids, GERD is a likely culprit, but still warrants evaluation by a doctor to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other issues. It may be linked to enzyme deficiencies as well.

The Role of Esophageal Motility Disorders

Beyond simple acid reflux, underlying esophageal motility disorders can contribute to chest pain and referred pain patterns. Achalasia is one example—a rare disorder where the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to relax properly, making it difficult for food to pass into the stomach. This leads to food accumulating in the esophagus, causing pressure and discomfort that can mimic cardiac pain. Another common issue is diffuse esophageal spasm, characterized by uncoordinated contractions of the esophageal muscles, resulting in chest pain that can be indistinguishable from angina.

These motility disorders often require specialized diagnostic testing—such as manometry (measuring esophageal pressures) and barium swallow studies—to identify the underlying problem. Treatment strategies differ significantly from standard GERD management; for example, achalasia may necessitate endoscopic dilation of the LES or even surgery to relieve the obstruction. Recognizing these conditions is important because treating only the reflux aspect won’t address the root cause of the pain. Understanding esophagitis can help in diagnosis.

Impact of Anxiety and Psychological Factors

The experience of chest pain, regardless of its source, can be incredibly anxiety-provoking. When individuals mistakenly attribute GERD-related pain to a heart condition, it creates a cycle of fear and hypervigilance. This heightened awareness of bodily sensations can amplify the perceived intensity of the pain and lead to panic attacks, further exacerbating symptoms. Anxiety itself can also contribute to chest tightness and discomfort, making it even more challenging to differentiate between GERD-related pain and cardiac pain.

Managing anxiety is therefore a crucial part of the overall treatment approach. Techniques like deep breathing exercises, mindfulness meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help individuals cope with their fears and reduce the psychological impact of chronic pain. It’s important to remember that feeling anxious about chest pain doesn’t invalidate the physical sensation; it simply highlights the complex interplay between mind and body in pain perception. Exploring gut pain and emotional triggers is beneficial here. The link between hormones and stomach pain should also be considered. Furthermore, the potential impact of gut pain and additives can play a role. Finally, liver regeneration is an important consideration for overall health and well-being. A holistic approach addresses both the physiological and psychological aspects of the condition, leading to improved quality of life.