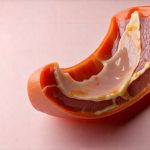

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an incredibly common condition affecting millions worldwide, often presenting as frequent heartburn or acid indigestion. While many experience GERD as a manageable nuisance, chronic, untreated GERD can lead to significant complications, and one of the most concerning is the development of esophageal strictures. These narrowings of the esophagus – the tube connecting your mouth to your stomach – can create substantial difficulty swallowing and significantly impact quality of life. Understanding how this progression occurs is crucial for both prevention and effective management of the condition. This article will delve into the intricate relationship between long-term GERD and esophageal stricture formation, exploring the mechanisms involved, diagnostic approaches, and available treatment options.

The underlying issue isn’t simply acid exposure, though that’s a primary driver. It’s the chronic inflammation resulting from repeated episodes of reflux. When stomach acid repeatedly backs up into the esophagus, it irritates the delicate lining. Over time, this constant irritation doesn’t just cause discomfort; it triggers a healing response within the esophageal tissue itself. Unfortunately, that ‘healing’ often involves scarring and fibrosis—the excessive build-up of fibrous connective tissue. This is where the potential for stricture development begins. The body’s attempt to repair damage ultimately leads to narrowing of the esophageal passage, making swallowing progressively more difficult. Considering how your body reacts over time, you might want to read same food .

Understanding the Progression: From GERD to Strictures

The journey from occasional heartburn to a full-blown esophageal stricture isn’t usually rapid. It typically unfolds gradually over years of untreated or poorly managed GERD. The initial stages often involve mild discomfort, perhaps experienced after certain foods or at night when lying down. As reflux continues unchecked, the inflammation becomes more persistent and widespread. This chronic inflammation initiates a cascade of events that ultimately lead to structural changes within the esophageal wall. The esophagus is not designed to withstand repeated acid exposure; its lining lacks the protective mechanisms found in the stomach.

A key factor driving stricture formation is metaplasia – a change in the type of cells lining the esophagus. In response to chronic irritation, normal squamous cells can transform into intestinal-type cells (a process called Barrett’s esophagus, which carries its own set of concerns). While not all individuals with Barrett’s will develop strictures, it indicates significant and long-standing esophageal damage. This cellular change is often accompanied by fibrosis, where the body deposits collagen fibers in an attempt to repair the damaged tissue. These fibrous bands progressively constrict the esophageal lumen. It’s also important to consider become intolerant over time.

The location of a stricture can also vary. They are most commonly found in the lower esophagus, near the junction with the stomach. However, they can occur anywhere along the length of the esophagus, impacting the severity and nature of swallowing difficulties. Importantly, strictures aren’t always complete blockages; they can range from mild narrowing to severe obstruction, requiring intervention. Early detection is vital because milder strictures are easier to manage than those that have significantly narrowed or become complex. You might also want to understand gut sensitivities.

Recognizing the Symptoms

Identifying a developing esophageal stricture early on requires awareness of subtle changes in swallowing ability. Initially, individuals might notice dysphagia – difficulty swallowing solid foods. This often begins with larger pieces of food getting ‘stuck’ momentarily before passing down. As the stricture worsens, it can progress to difficulty swallowing even soft foods or liquids. Here are some key symptoms to watch out for:

- Sensation of food sticking in the throat or chest

- Regurgitation of undigested food

- Coughing or choking during meals

- Feeling full quickly after eating small amounts

- Heartburn that doesn’t respond well to over-the-counter medications

- Unintentional weight loss (a sign of a more severe stricture)

It’s important not to dismiss these symptoms as ‘just heartburn.’ Persistent difficulty swallowing warrants medical evaluation. A healthcare professional can accurately diagnose the problem and recommend appropriate treatment. Often, initial assessments involve an upper endoscopy – a procedure where a thin, flexible tube with a camera is inserted into the esophagus to visualize the lining directly. If you are experiencing chronic fatigue, it may be related to food sensitivities.

Diagnostic Methods & Endoscopic Evaluation

Upper endoscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosing esophageal strictures. During this procedure, the physician can not only identify the location and severity of the narrowing but also assess for other complications like Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer. The endoscope allows for direct visualization of the esophageal lining, revealing any structural abnormalities. Biopsies can be taken during the endoscopy to evaluate the cellular changes occurring within the esophageal tissue.

Beyond endoscopy, other diagnostic tools may be used:

- Barium Swallow (Esophagram): This involves drinking a barium solution which coats the esophagus and allows it to be visualized on X-ray. It’s useful for identifying areas of narrowing but doesn’t provide as much detail as endoscopy.

- Manometry: This test measures the pressure within the esophagus during swallowing, helping to assess esophageal motility (how well food moves down). This isn’t directly used to diagnose strictures but can help rule out other causes of dysphagia.

During endoscopic evaluation, the physician will also grade the severity of the stricture. Strictures are typically categorized based on their degree of narrowing, influencing treatment decisions. Mild strictures may be managed with dietary modifications and medication, while more severe strictures often require dilation—a procedure to widen the esophageal passage (discussed below). You can learn about gut friendly eating to improve your overall digestive health.

Treatment Options: Dilation & Beyond

The primary goal of treatment is to restore adequate swallowing function and prevent further complications. The most common approach for treating esophageal strictures is endoscopic dilation. This involves using various tools inserted through an endoscope to gently stretch the narrowed portion of the esophagus. Several dilation methods exist:

- Balloon Dilation: A balloon catheter is inflated within the stricture, gradually widening it. This is often preferred for milder to moderate strictures.

- Bougie Dilation: A series of progressively larger plastic or metal rods (bougies) are passed through the stricture, mechanically stretching it.

- Self-Expanding Metallic Stents (SEMS): In cases of severe and complex strictures that are difficult to dilate, a SEMS may be placed temporarily to hold the esophagus open. These are typically used as a bridge to more definitive treatment or in patients who cannot tolerate repeated dilation procedures.

Dilation isn’t a one-time fix. Strictures can recur, requiring repeat dilation sessions. Alongside dilation, ongoing management of GERD is crucial. This includes:

- Lifestyle Modifications: Avoiding trigger foods (e.g., spicy, fatty, acidic foods), elevating the head of the bed during sleep, losing weight if overweight, and quitting smoking.

- Medications: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 receptor antagonists to reduce stomach acid production. These medications help minimize further esophageal irritation.

- Surgery (Fundoplication): In some cases, surgical intervention may be necessary to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter and prevent reflux – particularly if medical management fails or there are significant complications like Barrett’s esophagus.

It’s important to remember that esophageal strictures are a consequence of untreated GERD. Proactive management of reflux symptoms—through lifestyle changes and appropriate medication—is the best way to prevent their development. If you experience persistent heartburn or difficulty swallowing, seek medical attention promptly to avoid long-term complications. It may also be helpful to consider if your gut can adjust to certain foods over time.