The modern Western diet and lifestyle are characterized by a pervasive state of low-grade inflammation – often called “metaflammation” – which has become increasingly recognized as a key driver in the development of numerous chronic diseases. This isn’t the acute, localized inflammation that arises after an injury; instead, it’s a systemic, smoldering inflammatory response triggered by factors like processed foods, sedentary behavior, chronic stress, and gut dysbiosis. While seemingly benign, this constant low-level inflammation profoundly impacts the delicate ecosystem of our gut, specifically the mucosal barrier, ultimately disrupting digestion and nutrient absorption. Understanding this intricate relationship between chronic inflammation and gut health affects is crucial for proactive well-being and preventative healthcare.

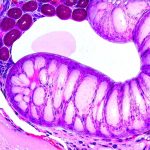

The gut mucosa – the inner lining of your digestive tract – acts as a highly selective barrier, meticulously controlling what enters the bloodstream while protecting the body from harmful substances. This barrier isn’t simply a physical wall; it’s a dynamic interface composed of epithelial cells, immune cells, and a diverse community of microorganisms (the microbiome). Constant low-level inflammation compromises this intricate system, leading to increased intestinal permeability – often referred to as “leaky gut.” When the mucosal barrier is weakened, larger molecules and even pathogens can slip through into the bloodstream, triggering an amplified immune response and perpetuating the cycle of inflammation. This creates a vicious loop where inflammation damages the gut, and a damaged gut exacerbates inflammation throughout the body.

The Inflammatory Cascade & Gut Mucosa Damage

Chronic low-level inflammation initiates a cascade of events that directly target and damage the gut mucosa. Key players in this process include pro-inflammatory cytokines – signaling molecules released by immune cells – such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1beta. These cytokines disrupt the tight junctions between epithelial cells, the structures responsible for maintaining barrier integrity. – This disruption leads to increased intestinal permeability, allowing undigested food particles, bacterial toxins (like lipopolysaccharide or LPS), and other harmful substances to cross into the bloodstream.

– The body’s immune system recognizes these foreign invaders, triggering a further inflammatory response and potentially leading to autoimmune reactions.

– Prolonged exposure to these triggers overwhelms the gut’s natural repair mechanisms, resulting in chronic mucosal damage and impaired barrier function. This isn’t merely a theoretical concern; studies have linked increased intestinal permeability to a wide range of conditions beyond digestive issues, including allergies, asthma, skin disorders, and even neurological problems. Understanding how gut inflammation affects energy is also vital for overall health.

The microbiome also plays a vital role in this process. A healthy gut microbiome supports the integrity of the mucosal barrier by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which nourish epithelial cells and strengthen tight junctions. However, chronic inflammation disrupts the balance of the microbiome – leading to dysbiosis, a state where harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial ones. Dysbiosis further weakens the gut barrier, increases inflammatory responses, and hinders SCFA production, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. The composition of your diet has a direct impact on this process; diets high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats promote dysbiosis and inflammation, while fiber-rich diets support a healthy microbiome and mucosal barrier function.

Consequences for Digestion & Nutrient Absorption

When the gut mucosa is compromised by chronic inflammation, digestive processes are significantly impaired, leading to indigestion, bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits. The reduced production of digestive enzymes—often caused by inflammation-induced damage to cells that produce them – hinders the breakdown of food molecules, making it harder for the body to extract nutrients. Furthermore, inflammation can affect gut motility (the movement of food through the digestive tract). – Slowed motility leads to constipation and fermentation of undigested carbohydrates, resulting in gas and bloating.

– Conversely, accelerated motility results in diarrhea and reduced nutrient absorption.

The impaired barrier function also affects nutrient absorption directly. As mentioned earlier, larger molecules can cross into the bloodstream, but so can nutrients themselves—often becoming bound to inflammatory compounds or being damaged during their passage through a compromised gut lining. This leads to deficiencies in essential vitamins, minerals, and amino acids, further weakening the body’s immune system and overall health. – Specific nutrients like vitamin D, iron, and B12 are particularly vulnerable to malabsorption in an inflamed gut.

– Chronic inflammation can also interfere with the absorption of fats, leading to steatorrhea (fatty stools) and deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K). The resulting nutritional imbalances contribute to fatigue, weakened immunity, and a host of other health problems.

Restoring Gut Health: Dietary Strategies

Addressing chronic inflammation and restoring gut health requires a multifaceted approach, with diet playing a central role. – Eliminate inflammatory foods: This includes processed foods, sugary drinks, refined carbohydrates, excessive alcohol, and unhealthy fats (trans fats, vegetable oils).

– Embrace an anti-inflammatory diet: Focus on whole, unprocessed foods like fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, healthy fats (olive oil, avocado, nuts, seeds), and fiber-rich foods. – A Mediterranean-style diet is often recommended due to its emphasis on these principles.

Increasing dietary fiber intake is crucial for promoting a healthy microbiome and strengthening the gut barrier. Fiber provides food for beneficial bacteria, leading to increased SCFA production. Foods like oats, beans, lentils, fruits, and vegetables are excellent sources of fiber. – Prebiotic foods (garlic, onions, asparagus) further support microbiome health by selectively feeding beneficial bacteria.

– Probiotic-rich foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi) introduce live microorganisms to the gut, helping to restore microbial balance. However, it’s important to note that probiotic supplements are not always effective for everyone and should be chosen carefully based on individual needs. – How gut health influences your overall well-being is a growing area of study.

The Role of Stress Management & Lifestyle Factors

While dietary changes are essential, addressing chronic inflammation requires more than just food choices. Chronic stress is a major contributor to inflammation, triggering the release of cortisol—a hormone that can disrupt gut barrier function and microbiome balance. – Implementing stress management techniques like mindfulness, meditation, yoga, or deep breathing exercises can help reduce cortisol levels and promote gut health affects your mental state.

– Regular physical activity also plays a role. Exercise helps reduce inflammation, improves gut motility, and supports a healthy immune system.

Sufficient sleep is another critical factor. Lack of sleep disrupts the microbiome, increases inflammation, and weakens the gut barrier. – Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night by establishing a regular sleep schedule, creating a relaxing bedtime routine, and optimizing your sleep environment. – Finally, minimizing exposure to environmental toxins (pesticides, pollutants) can also help reduce inflammatory burden on the body.

Future Directions in Gut Health Research

Research into the complex relationship between chronic inflammation and gut health is rapidly evolving. Emerging areas of investigation include: – Personalized nutrition: Tailoring dietary recommendations based on an individual’s microbiome composition and genetic predispositions.

– Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): Transferring fecal matter from a healthy donor to restore microbial balance in patients with severe gut dysbiosis. FMT is currently used for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection but is being explored as a potential treatment for other conditions.

- Targeted therapies: Developing drugs and supplements that specifically modulate the microbiome or strengthen the gut barrier. These include compounds like polyphenols (found in berries, green tea) and zinc carnosine (a combination of zinc and L-carnosine). As our understanding of the gut microbiome and its impact on health continues to grow, we can expect even more innovative approaches to preventing and treating inflammation-related digestive disorders. – How the gut affects your overall energy levels is also becoming clearer. Ultimately, prioritizing gut health is not just about relieving symptoms; it’s about investing in long-term overall well-being. – Consider looking into gut microbiome affects skin healing as well.