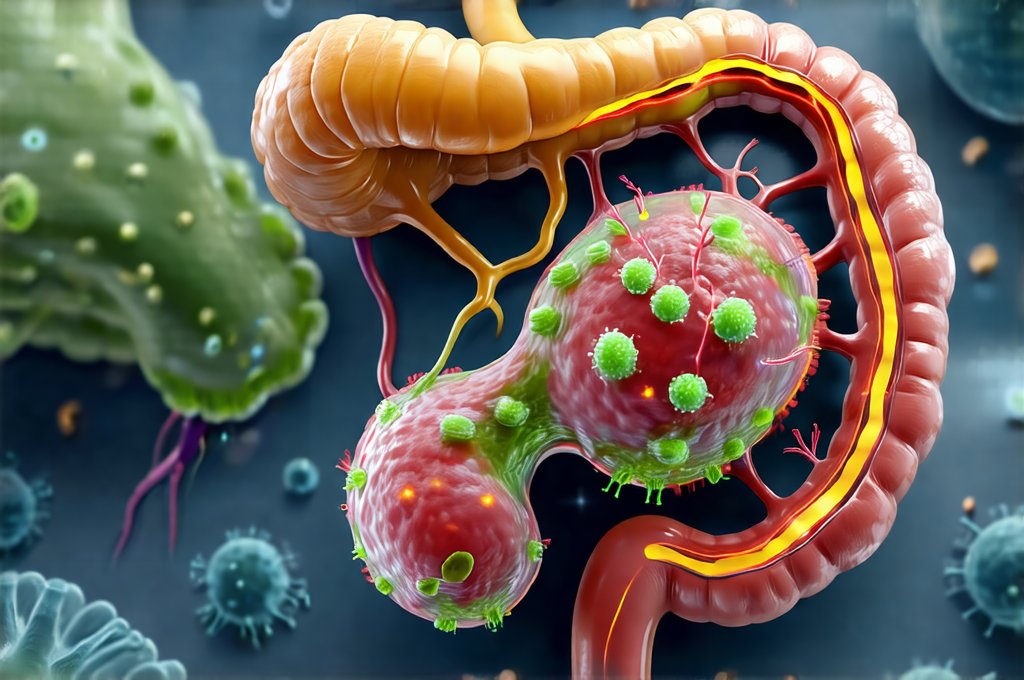

The common cold and influenza (flu) are ubiquitous illnesses, impacting individuals globally and often disrupting daily life. While we typically associate susceptibility with exposure to viruses like rhinovirus or influenza A/B, a growing body of research reveals that our internal ecosystem – the gut microbiota – plays a surprisingly significant role in determining how well we fend off these infections. For decades, immune function was largely viewed as a centralized system, primarily residing within organs like the thymus and spleen. However, it’s now understood that approximately 70-80% of our immune cells are located in or around the gut, making this region central to overall immunity. This intricate interplay between gut bacteria and the immune system profoundly influences our ability to resist viral invaders.

The relationship isn’t simply about ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ bacteria; it’s a complex dynamic where diversity and balance are key. A healthy gut microbiota fosters robust immune responses, enhances barrier function, and modulates inflammation – all critical factors in protecting against respiratory viruses. Conversely, dysbiosis (an imbalance in the gut microbiome) can weaken these defenses, making individuals more vulnerable to infection and potentially leading to more severe symptoms. Understanding this connection allows us to explore avenues for supporting our gut health as a proactive strategy for bolstering immune resilience during cold and flu season, and beyond.

The Gut Microbiota’s Influence on Immune Function

The gut microbiota isn’t merely a passive bystander; it actively educates and shapes the development of the immune system from early life. From birth onwards, exposure to diverse microbial communities helps ‘train’ the immune cells to distinguish between harmless commensal bacteria and harmful pathogens. This process is vital for preventing inappropriate immune responses that can lead to chronic inflammation or autoimmune diseases. Specifically, certain bacterial species stimulate the production of secretory IgA (sIgA), an antibody crucial for neutralizing viruses in the mucosal lining of the respiratory tract – our first line of defense against airborne infections.

Furthermore, gut bacteria influence both innate and adaptive immunity. The innate immune system provides a rapid, non-specific response to pathogens, while the adaptive immune system mounts a more targeted and long-lasting defense. The microbiota impacts innate immunity by stimulating the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) by intestinal cells, directly inhibiting pathogen growth. It also influences the maturation and function of immune cells like natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, enhancing their ability to recognize and destroy infected cells. In terms of adaptive immunity, gut bacteria help regulate T cell differentiation, promoting a balanced Th1/Th2 response which is crucial for effective antiviral immunity without excessive inflammation.

A diverse microbiome is demonstrably linked to stronger immune responses. Studies consistently show that individuals with greater microbial diversity are generally less susceptible to infections and experience milder symptoms when they do get sick. This highlights the importance of cultivating a balanced gut ecosystem through dietary choices, lifestyle factors, and potentially targeted interventions. The influence isn’t unidirectional; viruses themselves can also alter the composition of the gut microbiome, creating a feedback loop that affects immune function and disease severity. The Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Obesity offers more insight into this complex dynamic.

Modulation of Inflammation

Inflammation is a natural part of the immune response, but excessive or prolonged inflammation can be detrimental, contributing to tissue damage and hindering recovery. The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in regulating inflammatory processes. Dysbiosis, characterized by a decrease in beneficial bacteria and an increase in pro-inflammatory species, can lead to increased intestinal permeability – often referred to as “leaky gut.” This allows bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation. The Relationship Between Leaky Gut and Digestive Gas details how this impacts digestive health.

A healthy microbiome, conversely, promotes anti-inflammatory pathways. Certain bacterial groups produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate through the fermentation of dietary fiber. SCFAs have potent anti-inflammatory properties, strengthening the gut barrier, suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and enhancing immune cell function. Butyrate, in particular, is a key energy source for colonocytes (intestinal cells), promoting their health and integrity.

Maintaining gut microbial balance is therefore paramount for preventing chronic low-grade inflammation, which can weaken the immune system and increase susceptibility to infections. Interventions aimed at restoring microbiome diversity – like consuming prebiotic and probiotic-rich foods or considering targeted supplementation – may help dampen excessive inflammation and bolster antiviral immunity. The Link Between Gut Inflammation and Diarrhea explores the consequences of unchecked gut inflammation.

The Gut-Lung Axis

The connection between gut health and respiratory health is increasingly recognized as the “gut-lung axis.” This bidirectional communication pathway involves several mechanisms, including immune cell trafficking, microbial metabolite production, and shared mucosal surfaces. The lungs, like the gut, have their own microbiome, but it’s significantly influenced by the composition of the gut microbiota.

Microbial metabolites produced in the gut, such as SCFAs, can travel through the bloodstream to reach the lungs, impacting immune cell activity and modulating inflammation. Specifically, SCFAs promote the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the lungs, which suppress excessive inflammatory responses. Furthermore, the gut microbiome influences the recruitment and activation of alveolar macrophages, key players in lung defense against pathogens.

Disruptions in the gut microbiota have been linked to increased risk of respiratory infections, including asthma exacerbations and even severe outcomes from influenza. The Relationship Between Cold Symptoms and Digestive Issues highlights how systemic illness can impact digestion. Studies suggest that individuals with dysbiosis are more likely to experience prolonged viral shedding, indicating a compromised immune response in the lungs. This reinforces the idea that supporting gut health can indirectly strengthen lung defenses and reduce susceptibility to respiratory illnesses.

Dietary Strategies for Gut Health

Diet plays a fundamental role in shaping the composition of the gut microbiota. A diet rich in fiber is essential for promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria that produce SCFAs. Excellent sources include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts. Limiting processed foods, sugary drinks, and excessive amounts of red meat can help reduce populations of pro-inflammatory bacteria.

- Prebiotics: These are non-digestible fibers that act as food for beneficial gut bacteria. Examples include onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, bananas, and oats.

- Probiotics: These are live microorganisms found in fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha. While probiotic supplements can be helpful, obtaining probiotics through whole foods is often preferable due to the added benefits of other nutrients and fiber.

- Polyphenols: Found in colorful fruits and vegetables (berries, grapes, apples), green tea, and dark chocolate, polyphenols are metabolized by gut bacteria into beneficial compounds that have anti-inflammatory properties.

Hydration is also crucial. Water helps maintain a healthy mucosal lining in the gut and supports microbial diversity. Avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use is important as antibiotics can disrupt the gut microbiome, killing both harmful and beneficial bacteria. If antibiotic use is necessary, consider incorporating probiotic-rich foods or supplements after treatment to help restore balance. The Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Diabetes explains how gut health impacts overall metabolic processes.

Future Directions & Research

While our understanding of the gut microbiota’s role in cold/flu susceptibility has advanced significantly, there’s still much to learn. Ongoing research is exploring how specific bacterial strains can be targeted to enhance immune function and prevent viral infections. Personalized nutrition approaches, tailored to an individual’s unique microbiome profile, may hold promise for optimizing gut health and bolstering immunity.

Furthermore, researchers are investigating the potential of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as a therapeutic strategy for restoring gut microbial balance in individuals with dysbiosis. FMT involves transferring fecal matter from a healthy donor to a recipient, effectively repopulating their gut with beneficial bacteria. While FMT is currently used primarily for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, its potential applications in other areas of health – including immune support – are being actively explored. Finally, the role of virome (the collection of viruses within the gut) and how it interacts with the bacterial community will likely become a major area of focus in future research. The Relationship Between Gut Biome Diversity and Bloating Relief illustrates the benefits of a diverse microbiome. Ultimately, harnessing the power of the gut microbiota is poised to revolutionize our approach to preventing and managing respiratory infections. The Relationship Between Migraines and Digestive Upset demonstrates how interconnected the gut and overall health truly are.