The modern world presents an onslaught of stressors – from demanding jobs and financial pressures to relentless social media comparisons and environmental toxins. Increasingly, people are experiencing heightened rates of anxiety, panic attacks, and unpredictable mood swings. While psychological factors undeniably play a crucial role, emerging research suggests that the gut—often dismissed as merely a digestive organ—may be profoundly interconnected with mental wellbeing. This connection isn’t new; it’s rooted in what scientists call the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain. However, recent attention has focused on “leaky gut,” or increased intestinal permeability, as a potential trigger for these escalating mental health challenges, prompting investigation into how a compromised gut barrier impacts neurological function and emotional state.

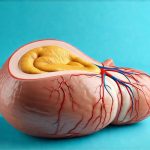

For decades, conventional wisdom largely separated physical illness from mental health. We treated anxiety and depression as primarily psychological issues, addressing them with therapy and medication focused on the brain. But this approach often overlooks crucial physiological factors. The gut is not simply where we digest food; it’s a complex ecosystem housing trillions of microorganisms—the gut microbiome—that profoundly influence our immune system, hormone production, and even neurotransmitter synthesis. A disruption in the delicate balance within the gut, particularly when the intestinal lining becomes more permeable (“leaky”), can set off a cascade of inflammatory responses that ultimately impact brain function and emotional regulation. Understanding this interplay is vital for a holistic approach to mental health.

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Two-Way Street

The gut-brain axis isn’t a single pathway, but rather a complex network involving multiple communication channels. One primary route is the vagus nerve, often referred to as the “wandering nerve,” which directly connects the gut and brain. Signals travel along this nerve in both directions: from the gut to the brain informing it about the state of digestion and microbial activity, and from the brain to the gut influencing digestive processes and immune function. Beyond the vagus nerve, the gut microbiome communicates with the brain through several other mechanisms:

- Production of neurotransmitters: The gut bacteria actively produce neurotransmitters like serotonin (often called the “happy hormone”), dopamine, and GABA, which play vital roles in mood regulation. In fact, an estimated 90% of serotonin is produced in the gut.

- Immune system modulation: A leaky gut allows undigested food particles and bacterial toxins to enter the bloodstream, triggering an immune response. Chronic inflammation, a hallmark of this process, has been strongly linked to anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders.

- Short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production: Beneficial gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber into SCFAs, which have anti-inflammatory properties and support brain health by providing energy for brain cells and strengthening the blood-brain barrier.

This constant two-way communication highlights how deeply interconnected our physical and mental states are. A healthy gut contributes to a balanced mood and clear thinking, while a compromised gut can significantly impact emotional wellbeing. The implications of this are substantial – it’s no longer sufficient to address anxiety or depression solely through psychological interventions without considering the health of the digestive system.

Leaky Gut: What It Is and How It Develops

“Leaky gut syndrome,” while not formally recognized as a medical diagnosis by all conventional practitioners, describes a condition where the tight junctions between the cells lining the intestinal wall become compromised, allowing larger molecules – undigested food particles, bacteria, toxins – to pass into the bloodstream. This triggers an immune response and systemic inflammation. While “leaky gut” itself is descriptive, it’s more accurately understood as increased intestinal permeability. Several factors can contribute to this increased permeability:

- Diet: A diet high in processed foods, sugar, unhealthy fats, and lacking in fiber can disrupt the balance of gut bacteria and damage the intestinal lining.

- Stress: Chronic stress significantly impacts gut health by altering microbiome composition and increasing intestinal permeability. The “fight or flight” response diverts blood flow away from the digestive system, hindering repair mechanisms.

- Medications: Certain medications, particularly antibiotics (which indiscriminately kill both beneficial and harmful bacteria), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can damage the gut lining.

- Infections: Gut infections, whether bacterial, viral, or parasitic, can disrupt the microbiome and contribute to increased permeability.

When the gut becomes “leaky,” these foreign substances entering the bloodstream trigger an immune response. The body identifies them as threats and launches an attack, leading to chronic inflammation. This systemic inflammation doesn’t just affect the gut; it travels throughout the body, including the brain, disrupting neuronal function and contributing to mood disorders.

Anxiety, Panic Attacks & Gut Health

The link between leaky gut and anxiety is becoming increasingly clear through research exploring the neurobiological mechanisms involved. Inflammation caused by a gut inflammation can disrupt neurotransmitter production, specifically serotonin and GABA, which are critical for regulating anxiety levels. Reduced serotonin activity is associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, inflammation directly impacts brain regions responsible for fear processing, such as the amygdala, making individuals more reactive to stressors and prone to panic attacks.

- Increased cortisol levels: Chronic gut inflammation can dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels – the stress hormone. Prolonged high cortisol contributes to anxiety, impaired cognitive function, and a weakened immune system.

- Brain fog & cognitive dysfunction: The inflammatory molecules released in response to a leaky gut can cross the blood-brain barrier, causing neuroinflammation and contributing to brain fog, difficulty concentrating, and memory problems—symptoms often associated with both anxiety and depression.

It’s important to remember that anxiety is complex. However, addressing gut health may offer an adjunct strategy for managing anxiety symptoms by reducing inflammation and restoring neurotransmitter balance. emotional triggers can exacerbate these issues.

Mood Swings & Emotional Instability

The rapid shifts in mood – from joy to sadness, irritability to calmness – often experienced by individuals with gut imbalances are also linked to the gut-brain axis. The microbiome influences the production of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation. An imbalanced gut can lead to fluctuations in dopamine levels, contributing to emotional instability.

The impact on the HPA axis is also significant. A leaky gut can create a cycle of chronic stress response – dysregulating cortisol release and making individuals more susceptible to mood swings. Additionally:

– Impaired nutrient absorption: Leaky gut can hinder the absorption of essential nutrients like B vitamins, magnesium, and zinc, which are crucial for neurotransmitter synthesis and emotional regulation.

– Microbiome imbalances impact brain plasticity: The microbiome influences neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to adapt and change. Imbalances in gut bacteria can impair this process, making it more difficult to cope with stress and regulate emotions effectively.

These factors combine to create a volatile internal environment that contributes to unpredictable mood shifts and emotional reactivity. gut pain can often worsen this instability.

Strategies for Supporting Gut Health & Mental Wellbeing

While addressing mental health requires a multifaceted approach, supporting gut health can be a powerful component of the healing process. Here are some strategies to consider:

- Dietary changes:

- Eliminate processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats.

- Increase fiber intake through fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Incorporate fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi into your diet (if tolerated). These provide beneficial probiotics.

- Stress management techniques:

- Practice mindfulness meditation or yoga to reduce stress levels.

- Prioritize sleep – aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep each night.

- Engage in regular physical activity.

- Supplementation (under the guidance of a healthcare professional):

- Probiotics: To restore beneficial gut bacteria.

- L-glutamine: An amino acid that helps repair the intestinal lining.

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Possess anti-inflammatory properties.

It’s crucial to work with a qualified healthcare professional—such as a functional medicine doctor or registered dietitian—to develop an individualized plan based on your specific needs and health history. Remember, healing the gut is often a journey, not a quick fix, but it can be a transformative step towards improved mental and physical wellbeing. Addressing both the psychological and physiological aspects of anxiety, panic attacks, and mood shifts offers the best path toward lasting resilience and emotional balance. menstrual cycle phases can also play a role in gut health. Understanding trapped gas and its impact is also important. Finally, consider the connection between perfectionism and gut reactions for a holistic approach.