Food is fundamental to life, yet for many, the act of eating can be fraught with anxiety, aversion, or even debilitating fear. What often seems like a simple psychological issue – a dislike of certain textures, an overwhelming worry about contamination, or a panic response to specific foods – may have roots far deeper than we previously understood. For years, mental health professionals focused primarily on cognitive and behavioral factors to explain these food-related challenges. However, emerging research is revealing a powerful and often overlooked connection between our gut microbiome – the trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms residing in our digestive tract – and our emotional and psychological state, specifically as it relates to how we perceive and interact with food. This bidirectional communication pathway, known as the gut-brain axis, is rapidly changing the way we approach understanding and potentially addressing these complex issues.

The traditional view of anxiety and aversion centered largely on learned behaviors, traumatic experiences, or underlying psychological conditions. While these factors undeniably play a role, they don’t fully explain the prevalence or intensity of food-related distress experienced by so many individuals. Increasingly, scientists are recognizing that the gut microbiome isn’t just passively present within us; it actively influences our brain chemistry, mood regulation, and even our perception of reward and safety. This influence can manifest in a variety of ways, from subtle feelings of unease around food to full-blown phobias and restrictive eating disorders. Understanding this interplay is crucial for developing more holistic and effective interventions that address the underlying biological mechanisms contributing to these challenges – not just the psychological symptoms.

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Two-Way Street

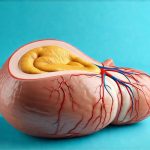

The gut-brain axis isn’t a single pathway, but rather a complex network of communication channels connecting the gastrointestinal tract with the central nervous system. This communication happens in several ways, including through the vagus nerve (a major cranial nerve running directly between the gut and brain), the immune system, the endocrine system (hormone production), and even the metabolites produced by gut bacteria themselves. When our gut microbiome is balanced and diverse – meaning it contains a wide range of beneficial bacterial species – it promotes optimal functioning of these communication channels. Conversely, an imbalanced microbiome (dysbiosis) can disrupt these pathways, leading to alterations in brain function and emotional regulation.

Dysbiosis has been linked to increased inflammation throughout the body, including the brain. Chronic inflammation is known to contribute to anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions. Furthermore, gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters – chemical messengers that play a critical role in mood and behavior – such as serotonin (often called the “happiness hormone”), dopamine (involved in reward and motivation), and GABA (an inhibitory neurotransmitter that promotes relaxation). An unhealthy gut microbiome can therefore directly impact our brain’s ability to regulate these essential chemicals. – This is why optimizing gut health could potentially influence mental wellbeing. Recognizing the connection between gut health is key to holistic wellness.

Importantly, this isn’t a one-way street. What we eat significantly impacts the composition of our gut microbiome. Highly processed foods, sugary drinks, and diets low in fiber can promote the growth of harmful bacteria while suppressing beneficial ones. Stress, antibiotics, and other factors can also disrupt the delicate balance of the gut ecosystem. This creates a vicious cycle: poor diet leads to dysbiosis, which contributes to anxiety, which may lead to further unhealthy eating habits, reinforcing the imbalance.

How Gut Bacteria Influence Food Aversion & Anxiety

Food aversion isn’t always about taste; it can be deeply rooted in anticipatory nausea – a feeling of sickness triggered by merely thinking about or seeing certain foods. Research suggests that gut bacteria play a role in this phenomenon. Specific bacterial species have been linked to increased sensitivity to visceral sensations (signals from the internal organs), making individuals more prone to experiencing nausea and discomfort even before consuming food. – This can contribute to avoidant eating behaviors, where people restrict their diets to only those foods they perceive as “safe”.

Furthermore, anxiety around food often stems from a fear of contamination or negative consequences like digestive upset. A dysbiotic gut microbiome can heighten the immune system’s reactivity, making individuals more sensitive to even minor irritants in food. This heightened sensitivity can trigger exaggerated feelings of discomfort and worry, leading to anxious thoughts and behaviors related to eating. Some studies have indicated that people with ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder) often exhibit altered gut microbiome compositions compared to healthy controls. – However, more research is needed to fully understand the causal relationship. Understanding IBS and its relation to the gut can help manage anxiety related to food.

The reward system in the brain also plays a crucial role. Gut bacteria influence dopamine production and signaling, which are essential for experiencing pleasure from food. An unhealthy gut microbiome can disrupt this system, leading to reduced enjoyment of food and potentially contributing to restrictive eating patterns or disordered eating behaviors. – This can create a negative feedback loop where food becomes associated with anxiety rather than satisfaction. It’s important to consider the connection between anxiety and digestive discomfort when addressing these issues.

The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are metabolites produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber. They’re not just waste products; they’re incredibly important signaling molecules that have far-reaching effects on health, including mental wellbeing. SCFAs like butyrate, propionate, and acetate cross the blood-brain barrier and directly influence brain function.

Butyrate, in particular, has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties and can enhance neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to adapt and change. – It also appears to play a role in regulating stress responses and reducing anxiety symptoms. A diet lacking in fiber limits SCFA production, potentially contributing to gut dysbiosis and increased vulnerability to anxiety and aversion.

Increasing dietary fiber intake – through foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes – is one way to support the growth of beneficial bacteria that produce SCFAs. However, it’s important to increase fiber gradually, as a sudden increase can cause digestive discomfort. – Prebiotic supplements (foods or supplements that feed beneficial gut bacteria) may also be helpful in some cases, but should be discussed with a healthcare professional. It’s useful to understand the connection between gut health and overall wellbeing when making dietary changes.

Exploring Potential Interventions: Beyond Psychology

While traditional therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and exposure therapy remain valuable for addressing food-related anxiety and aversion, the emerging understanding of the gut-brain axis suggests that interventions targeting the microbiome could offer complementary or even primary treatment strategies. – It’s crucial to emphasize that these are not replacements for mental health care but rather potential adjunct approaches.

One promising avenue is dietary modification. A diet rich in fiber, whole foods, and fermented foods (like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi) can promote a healthy gut microbiome. Reducing processed foods, sugar, and artificial sweeteners is also essential. Another approach gaining traction is the use of probiotics – live microorganisms that, when consumed in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. – However, probiotic supplements are not one-size-fits-all; different strains have different effects, and it’s important to choose products based on specific needs and under the guidance of a healthcare professional. The connection between overtraining and gut health is also relevant as stress can impact the microbiome.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) – transferring fecal matter from a healthy donor into the recipient’s gut – is an extreme intervention currently reserved for severe cases like recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, but research is exploring its potential in other conditions, including mental health disorders. – FMT is still experimental and carries risks, so it’s not widely available or recommended outside of clinical trials. Understanding gut biofilm can also help understand the complexities of gut health. Ultimately, a personalized approach that considers individual gut microbiome composition, dietary habits, and psychological factors will likely be the most effective strategy for addressing food-related anxiety and aversion. The connection between gut health and overall systemic inflammation is also important to consider.