The human gut is often described as our “second brain,” reflecting its profound influence on not just digestion but also mood, immunity, and overall well-being. While we typically associate gastrointestinal distress with food poisoning, infections, or underlying medical conditions, a less discussed – yet surprisingly common – phenomenon links heightened emotional vulnerability to changes in bowel function. This isn’t simply “nervousness” causing a slight upset stomach; it’s a complex interplay between the brain, the gut microbiome, and our physiological stress response, leading to symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to urgent defecation. Understanding this connection requires acknowledging the powerful bidirectional communication pathway known as the gut-brain axis, and how perceived threats – particularly those relating to social vulnerability or emotional exposure – can disrupt its delicate balance.

This article aims to explore the often-overlooked relationship between feeling emotionally vulnerable and experiencing loose bowel activity. It’s crucial to state upfront that this is not intended as medical advice. If you are consistently experiencing significant gastrointestinal distress, please consult a healthcare professional. We’ll delve into the neurobiological mechanisms at play, examine common triggers for vulnerability-induced bowel changes, and discuss strategies for managing these experiences – focusing on self-awareness, coping mechanisms, and when to seek support. This is about recognizing a natural physiological response, not pathologizing it, but empowering individuals to understand and navigate this sensitive area of their health.

The Gut-Brain Axis & Emotional Regulation

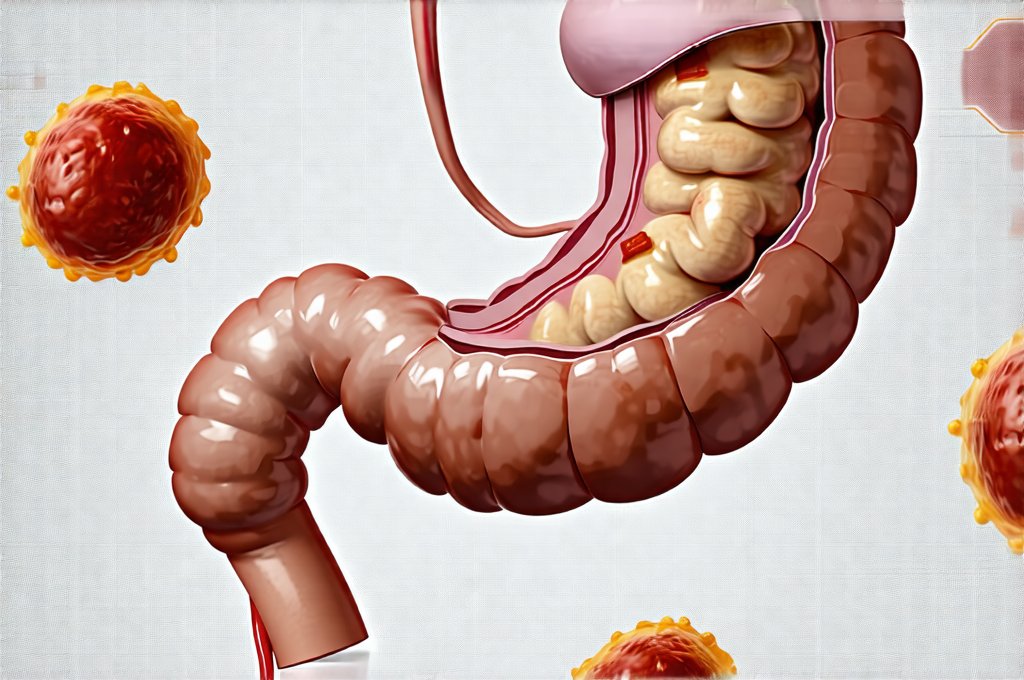

The gut-brain axis isn’t merely metaphorical; it’s a demonstrable network involving neural, hormonal, and immunological pathways. Information constantly flows in both directions: the brain influences gut motility, secretion, and even microbiome composition, while the gut provides feedback to the brain about nutrient status, inflammation levels, and microbial activity. This constant communication is vital for maintaining homeostasis. When we experience emotional stress – especially vulnerability – it triggers a cascade of physiological changes designed to prepare us for “fight or flight.” This includes activation of the sympathetic nervous system, releasing hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. While these responses are crucial for survival, they can also profoundly impact gut function.

Specifically, cortisol can alter intestinal permeability (often referred to as “leaky gut”), increase visceral hypersensitivity (heightened awareness of sensations in the gut), and disrupt the delicate balance of the gut microbiome. A disrupted microbiome is linked to a variety of health issues, including increased inflammation and altered bowel habits. The brain interprets signals from the gut, and the gut responds to signals from the brain – creating a feedback loop that can quickly escalate if vulnerability is perceived or experienced. It’s not just what happens that matters, but how we perceive it; our subjective experience of vulnerability heavily influences the physiological response.

Furthermore, emotional regulation plays a key role. Individuals with difficulty processing and managing emotions may be more susceptible to these gut-related responses. This isn’t about weakness – it’s about the capacity to modulate the stress response. Chronic emotional suppression or unresolved trauma can also contribute to heightened sensitivity within the gut-brain axis. The result is that feelings of exposure, inadequacy, or fear can manifest not only as psychological distress but also as physical symptoms like diarrhea, urgency, or abdominal cramping. Understanding how loose bowel days can be linked to emotional stress is key.

Triggers and Vulnerability Profiles

Vulnerability isn’t a monolithic experience; it manifests differently for everyone. Identifying personal triggers is essential to understanding how emotional vulnerability impacts your gut health. Common triggers include:

- Social situations involving public speaking or performance.

- Intimate relationships and the fear of rejection or intimacy.

- Professional settings where feedback, evaluation, or competition are prevalent.

- Situations that evoke past trauma or feelings of helplessness.

- Moments requiring self-disclosure or expressing personal opinions.

The types of vulnerabilities individuals experience also differ considerably. Some may be highly sensitive to criticism, others to abandonment, and still others to feeling out of control. This “vulnerability profile” – the specific areas where someone feels most exposed – shapes the type and intensity of their physiological response. For example, someone with a strong fear of judgment might experience bowel urgency during a presentation, while someone who fears losing control might have diarrhea when faced with unexpected changes to their schedule.

It’s important to recognize that anticipatory anxiety can be just as potent a trigger as the actual event itself. Worrying about potential vulnerability – imagining worst-case scenarios or dwelling on past negative experiences – activates the stress response and can lead to preemptive bowel activity. This is why individuals sometimes experience symptoms before a triggering event even begins. The brain, anticipating threat, prepares the body for it, often resulting in unwanted gastrointestinal consequences. It’s helpful to remember that poor food combining can also exacerbate these issues.

Understanding the Physiological Cascade

The physiological process unfolding during vulnerability-triggered loose bowel activity involves several interconnected steps:

- Perception of Threat: The amygdala – the brain’s “fear center” – identifies a potential threat to emotional well-being (e.g., impending social interaction, critical feedback).

- Activation of the Sympathetic Nervous System: This triggers the release of adrenaline and cortisol, initiating the fight-or-flight response. Heart rate increases, breathing becomes faster, and blood flow is diverted from non-essential functions (like digestion) to muscles.

- Increased Gut Motility: The sympathetic nervous system accelerates intestinal contractions, pushing waste through the digestive tract more quickly. This reduces time for water absorption, leading to looser stools.

- Altered Intestinal Permeability: Cortisol can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier, allowing undigested food particles and toxins to enter the bloodstream, potentially triggering inflammation and further gut disruption.

- Visceral Hypersensitivity: Heightened sensitivity in the gut makes individuals more aware of normal digestive processes, which can be misinterpreted as discomfort or urgency.

This cascade happens rapidly, often within minutes of perceiving a threat. The intensity of the response depends on several factors, including the perceived severity of the vulnerability, an individual’s baseline stress levels, and their history of emotional regulation skills. It’s also important to remember that habituation can play a role; repeated exposure to triggering situations may lead to increased sensitivity over time. Sometimes poor sleep hygiene can worsen symptoms as well.

Coping Strategies & Self-Awareness

Managing loose bowel activity triggered by vulnerability requires a multi-faceted approach focusing on self-awareness, coping mechanisms, and, if necessary, professional support. The first step is recognizing the connection between emotional state and gut function – identifying patterns and triggers specific to your experience. Keeping a journal can be incredibly helpful in tracking these connections.

- Mindfulness & Grounding Techniques: Practices like deep breathing exercises, meditation, or progressive muscle relaxation can help calm the nervous system and reduce anxiety. Grounding techniques, such as focusing on physical sensations (e.g., feeling your feet on the floor) can bring you back to the present moment and interrupt the cycle of worry.

- Cognitive Restructuring: Challenging negative thought patterns and reframing triggering situations can lessen their emotional impact. For instance, instead of thinking “I’m going to embarrass myself during this presentation,” try “This is an opportunity to share my ideas, even if I feel nervous.”

- Self-Compassion: Treating yourself with kindness and understanding – especially when experiencing vulnerability or physical symptoms – can mitigate the emotional impact. Recognize that everyone experiences anxiety and discomfort; it’s a normal part of being human.

- Gradual Exposure: Carefully exposing oneself to triggering situations in small, manageable steps can help desensitize the nervous system over time.

When To Seek Professional Support

While many individuals can manage vulnerability-induced bowel changes with self-care strategies, there are times when professional support is essential. If symptoms are severe, persistent, or significantly impacting your quality of life, it’s crucial to consult a healthcare provider.

- Rule out Underlying Medical Conditions: It’s important to ensure that the symptoms aren’t caused by an underlying medical issue (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease).

- Mental Health Support: A therapist or counselor can help address underlying emotional issues, develop coping mechanisms for managing anxiety and vulnerability, and explore trauma history if relevant. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) are particularly effective approaches.

- Gut-Directed Hypnotherapy: This technique uses hypnosis to retrain the brain’s response to gut sensations and reduce visceral hypersensitivity.

- Dietary Adjustments: While not a cure, making dietary changes – such as reducing caffeine or avoiding trigger foods – may help minimize symptoms in some individuals. However, avoid restrictive diets without professional guidance. Consider if excess fresh juicing is a factor for you as well.

Remember, seeking help is a sign of strength, not weakness. Addressing the emotional and physiological components of this complex relationship can lead to improved well-being and a greater sense of control over your health. If changes in location are triggering issues, consider bowel inconsistency triggered by moving. Also remember that stress induced eating can contribute to these issues.